There is no available reason to believe that a national level roll-out of insurance under the proposed NHPS will have any less of the issues that have plagued state schemes.

A woman, who underwent a sterilisation surgery at a government mass sterilisation camp, feeds her child while sitting on a hospital bed for treatment in Bilaspur, in Chhattisgarh November 14, 2014. Credit: Reuters/Anindito Mukherjee

The government’s new National Health Protection Scheme (NHPS) is being rolled out rapidly by the NITI Aayog. It is essentially a massive insurance scheme, announced in this year’s Budget. As the government pushes ahead, a few lessons from states like Chhattisgarh could be instructive.

Chhattisgarh is considered a ‘well-performing’ state under the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY). It has one of the highest coverage of families under insurance (more than 80% covered). The state has combined the RSBY (for below poverty line or BPL) with the state government-funded scheme for non-BPL, thus having ‘Universal Health Insurance’. With seemingly high political commitment, one would expect that insured people in Chhattisgarh would be protected from hospitalisation expenditure.

But the evidence says that insured patients are often forced to make illegal payments, money is being drained to private hospitals at the expense of the poor and a nexus between the public sector and private sector is developing.

The basic modalities of the government’s new scheme would be the same as in existing schemes like RSBY – the insurance premium would be paid by the government per family to an insurance company (like in Chhattisgarh) or a trust (like in Andhra Pradesh). The company or trust will empanel public and private hospitals, which will provide ‘cashless’ hospital services and get the claim amount on the basis of pre-determined packages.

One of the main aims of any such health scheme is to reduce the financial burden on patients for hospitalisation and protect them from catastrophic health expenditure. So what has been the experience of existing health insurance schemes like in Chhattisgarh toward providing ‘cashless’ hospitalisation care?

Also Read: NITI Aayog Comes to the Rescue As Health Ministry Clueless on ‘World’s Largest Healthcare Programme’

Insured patients forced to make illegal payments

In Chhattisgarh, the draft memorandum of understanding (MoU) between hospitals and insurance companies selected by the government states that empanelled hospitals will have to provide ‘cashless’ services. The MoU states “The Institution shall provide cashless facility to the beneficiary in strict adherence to the provisions of the agreement”.This means that the hospital is not allowed to take any money from the patient but will charge the insurance company as per the predetermined package rate, which includes all charges.

However, from our work in Chhattisgarh, we have seen many cases like this: For example, in March 2017, Rajmati* of Birgaon went to a private hospital in Raipur for delivery and delivered by C-section. The hospital charged Rs 17,000 on her health insurance card and made her pay an additional Rs 10,000 in cash.

Likewise, Premkali Sahu* (62) went for a cataract operation to a private hospital in Raipur in March 2017. The hospital charged Rs 7,000 to her health insurance card and took Rs 8,000 from her in cash.

In Chhattisgarh, patients who have sought redressal regarding illegal payments, say that they get sympathy but no solution – “Helpline par phone karne se sahanubhuti milti hai samadhaan nahi”, (If we call the helpline, we get sympathy, not a solution) said one patient.

These experiences show that private hospitals do, in fact, force people to make illegal payments. These are not unique experiences, these are the norm. This is also borne out by studies.

Our previous study on slums in Raipur found that nearly all (96%) had to spend money for hospitalisation, even if they were insured. A recent study using the government’s National Sample Survey (NSS) data shows that even when people were insured, 95% of them going to the private sector incurred costs for hospitalisation, with the average (median) expenditure of Rs 10,000.

The only thing that made any difference to their out-of-pocket costs was if they went to a government hospital – though 66% of the insured people who went to government hospitals had to spend from their pocket, the average (median) amount (Rs 1,200) was eight times less than that in the private sector.

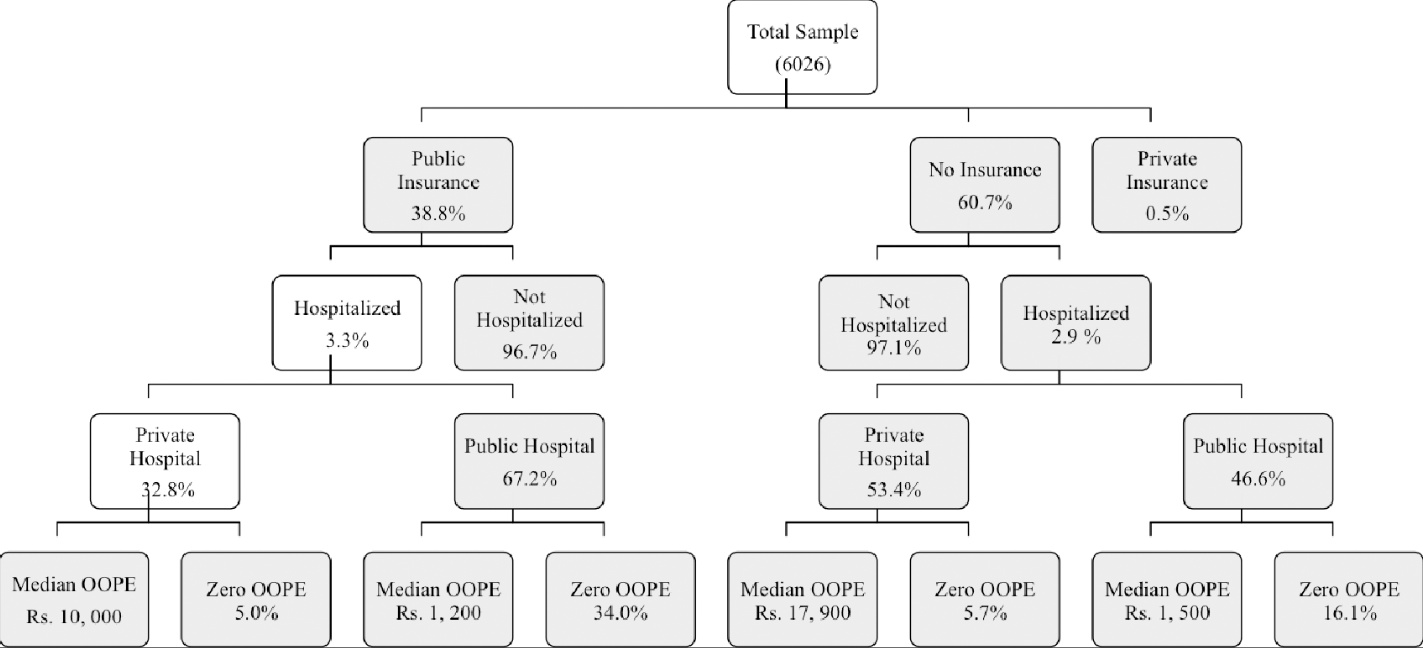

And though the uninsured incurred even higher expense, being insured did not protect most from financial burden. The summary of findings from the Chhattisgarh NSS study is presented in the diagram below.

Of the total households (insured and uninsured) who had at least one person hospitalised, a shocking one third (35.5%) incurred catastrophic health expenditure due to hospitalisation costs, which means that these families faced a risk of becoming poorer due to the expenditure.

Summary of findings (Nandi et al 2017). Source: PLOS One

Studies from other states and for the whole of the country (see here, here, here and here) similarly show that RSBY has not been able to protect people from financial burden due to hospitalisation costs and may have, in some cases, increased it.

The poor and the public lose out

There is a big contradiction between the stated aims of the new policy and the data on how the schemes have actually worked.

The policy says it will cater to 10 crore of the poorest families. The data says that it is often private hospitals, in urban areas, which get the most number of claims. These hospitals deal with a fraction of those who need healthcare. But the government still insists their insurance scheme will cover 50 crore people.

Evidence from many states shows that a higher proportion of the insurance funds are going to the private sector. Studies show the private sector getting 75% of the insurance funds in Andhra Pradesh (with corporate hospitals taking the biggest chunk) and Maharashtra, and 65% of the claims amount in Tamil Nadu. Only Kerala seems to be an exception, where even the NITI Aayog says that 55% of the total money goes back to the public sector.

This is because the insurance money, which is supposed to ‘follow the patient’, is in reality, ‘following’ the private hospitals.

These private hospitals are concentrated in urban centres, and as a result, most of the insurance money is being claimed there, with rural areas getting very little additional services.

In Chhattisgarh, the three cities of Raipur, Bilaspur and Durg together host 63% of the empanelled private hospitals. The 12 tribal-dominated districts received only 16% of insurance claims. The CEO of a large private insurance company recently observed that most people to be ‘targeted’ under the NHPS belong to remote districts which have few private facilities.

Also Read: Why the Poor Will Not Be the True Beneficiaries of the ‘World’s Largest Health Programme’

Moreover, a number of private hospitals are engaging in cherry-picking, i.e. selectively admitting only ‘profitable’ cases, undertaking irrational hospitalisations and unnecessary surgeries. Also, some conditions that could be treated at the primary level are now being shifted to the secondary and tertiary levels. These trends are not good for patients or for ‘public health’.

The NSS study shows that in Chhattisgarh, more people utilised the public sector for hospitalisation, even when insured. It also showed that the Scheduled Tribes, rural and poor populations and women were predominantly utilising the public sector. However, the insurance claims data shows that 83% of the claims amount is going to the private sector.

This means that while on the one hand, the poor and other vulnerable groups are utilising government hospitals more, public funds are being diverted to the private sector through the insurance scheme.

Learning from evidence and experience, there is no available reason to believe that a national level roll-out of insurance will have any less of the issues that have plagued state schemes like that of Chhattisgarh.. Credit: Reuters/Mukesh Gupta

Distorting the public health system

What logic does the NITI Aayog have, when they say that the government should not directly fund the public sector, but funds should instead be routed through intermediaries with vested interests?

In their presentation to journalists following the Budget announcement, they said the NHPS would have a vision of ‘Galvanising the public sector through NHPS’.

But they are not answering this question: what would be the value addition to the public sector through NHPS over directly funding the public sector?

In Chhattisgarh, the budget for health insurance has been increasing year after year while an under-resourced public sector is struggling for funds. The insurance scheme is leading to further distortions in the public health system.

Take the case of Rambai*. She went to the urban Primary Health Centre near her house soon after her labour pain started. The health staff there said that she would need an operation. Though the Raipur Medical College Hospital was not far, the government health staff told her to go a nearby private nursing home. Conversations with others of the locality revealed that this was a common practice. But it cost Rambai dearly. The nursing home took Rs 10,000 cash from the family in addition to charging from the insurance card.

Doctors at a district hospital regularly tell all pregnant women to get a sonography done under the ante-natal-care insurance package at a particular private hospital. They give them slips with the name of the private hospital. The women complained that in addition to charging it to the insurance card, the clinic takes illegal payments (Rs 600) from them.

The insurance scheme is thus furthering the nexus between the private sector and health personnel in the public system. Moreover, private practice by government doctors is still unregulated in Chhattisgarh despite a High Court order restricting it. Though a proportion of the insurance claim money is given as incentives to government doctors, it is more ‘profitable’ for them to refer patients to private hospitals that they are associated with.

Another damage to the public health system has been in terms of undermining its ‘universal’ nature. People are supposed to be treated in the government facilities anyways, even without using health insurance. However, anecdotal evidence shows that the introduction of health insurance may be posing an additional barrier to accessing healthcare in the public sector.

Recently, in Maharashtra, a paralysed eight-year-old Adivasi child who had travelled 467 km to a tertiary-level public hospital in Mumbai, where she should have received healthcare anyway, was denied treatment for many days as she was not enrolled under the state health insurance scheme.

Government promoting private sector but not regulating it

Learning from evidence and experience, there is no available reason to believe that a national level roll-out of insurance will have any less of the issues that have plagued state schemes like that of Chhattisgarh.

Yet if the government pushes along with this, can there be any safeguards put in place for patients?

What the government is doing through insurance, is indirectly funding the private sector. From the studies presented above, it is clear that the bulk of the insurance claims will be going to the private sector hospitals, clustered in urban areas and catering only to a few.

The government has had enough opportunities to regulate the private sector. The Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act 2010 remains un-implemented in most states and has been met by opposition from private sector doctors and their associations.

In short, this is what India is getting from the “world’s largest healthcare programme”: While the public sector weakens, the private sector grows in strength, amply fuelled by the government’s patronage, but the needed regulation of this sector is absent. And in all of this, patients have no voice or choice. With the NHPS, patients don’t have any real healthcare, and only have the promise of health insurance.

*Names changed to protect privacy

Sulakshana Nandi, Deepika Joshi and Sangeeta Sahu are public health researchers and activists working in Chhattisgarh