Bodies like JNU’s GSCASH sensitise and create dialogue on gender and sexual politics at the university, and on how this interplays with other social and cultural locations and identities.

Kolkata: Students of Jadavpur University hold placards as they participate in a rally to protest against sexual harassment of women, in Kolkata. Credit: PTI

Despite there being regular reports of sexual harassment at university campuses across the country, the first elected committee set up by a university to deal with such cases on its campus, in line with the Supreme Court’s landmark Vishaka in 1997, was dissolved by university authorities last month. The two processes are not disconnected and the reason lies at the crossroads of what is perceived as a ‘threat’, which in turn creates the need to control, and herein lies the potential of transforming campus politics across the country.

Participatory process

On May 2, 2016, the University Grants Commission (UGC) notified the UGC (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal of Sexual Harassment of Women Employees and Students in Higher educational institutions) Regulations 2015. This notification was the basis of a decision by the executive council at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU. Subsequently, on September 18, a notification from the JNU registrar announced the ‘replacement’ of the Gender Sensitisation and the Committee for the Prevention of Sexual Harassment (GSCASH) by the internal complaints committee (ICC). Challenging the move, students and teachers filed a writ petition in the Delhi high court with the help of a legal team led by senior Supreme Court advocate Indira Jaising. The court ordered an interim stay on the sealing of the GSCASH office by the ICC, followed by affixing a second lock by the GSCASH. The next hearing on this matter is on October 3. The hearing on the main petition is scheduled for November 28.

I was a masters student at JNU when the first student elections to GSCASH was held in 1999. Many of us participated in it, for a separate and a specific political space was being created to break the silence around sexual violations and infringements in the campus. At that time, the GSCASH elections were held simultaneously with the JNU Students’ Union (JNUSU) elections. This helped weave women’s issues with student politics, just as rape and domestic violence had acquired a public, political visibility since the early 1980s through women’s movements. But since 2008, GSCASH and JNUSU elections were held separately, primarily because the latter was operating within the Lyngdoh Committee regulations.

I was an external member of GSCASH between August 2014 and August 2017, representing the ‘woman academician’ category. My experience as part of multiple enquiry committees prompts me to reflect upon two questions.

One of my first concerns with the ICC sealing the GSCASH office was how the confidentiality of all the present and the past cases gets affected. The GSCASH office is not merely a physical space; it represents a certain history and culture of democratic functioning, meticulous maintenance of records, while ensuring due process and the anonymity of complainants and the details of the cases (thereby extending the confidentiality principle to the defendants, the witnesses and all other parties involved with a particular complaint). The GSCASH office was symbolic of the faith and the confidence that the students, faculty and administrative staff of JNU extended towards it. Sealing the office destroys the democratic spirit that GSCASH represented in JNU.

More importantly, can the ICC really replace GSCASH? The petition and its arguments are extremely compelling on this matter. If the Delhi high court upholds the petition, it will go a long way in ensuring that the participatory processes through which many universities came up with their own anti-sexual harassment and sensitisation committees, cannot be thwarted by just a notification from the vice-chancellor, apparently based on a UGC notification.

A protest in JNU in defence of GSCASH on September 18. Credit: Facebook/Samir Asgor Ali

A ‘democratic’ committee

The gangrape of a woman employee during work, multiple protests by women’s groups across the country, a writ petition filed by an organisation in the Supreme Court and the subsequent judgement (Vishaka v State of Rajasthan) defined sexual harassment of women at the workplace for the first time in 1997. The court responded to demands made by women’s movements and addressed the empirical reality of women workers in organised workforce, which led to the idea of creating a university-specific prevention and grievance redressal body in JNU. Although, in 2013, a specific legislation, the Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, Redressal) Act, 2013, enacted by the parliament brought the domestic worker within the ambit of the legislative protection, the woman student was ironically outside the ambit of a statute. That moment in law reform came in 2013, post the 2012 Delhi gang rape, initiated again by widespread protests across the country. These protests and demands took the shape of multiple legal reforms through the Criminal Law Amendment Act 2013, some of which were in response to the recommendations made by the Verma Committee.

The Verma Committee report mentions:

We are also aware that in compliance with the judgment in Vishakha v. State of Rajasthan, universities such as the Jawaharlal Nehru University and the University of Delhi have formulated policies and constituted mechanisms to prevent and redress complaints of sexual harassment. We have taken note of the suggestion that those universities whose anti-sexual harassment policy rules and committee mechanism meet the standards of Vishakha are proposed to be exempted from the purview of the Sexual Harassment Bill, 2012, as these committees are more democratic and are better related to ensure prevention and prohibition of sexual harassment in educational institutions. [pp 119 of the Report]

Those universities, in which Internal Complaint Committees have functioned successfully to deal with sexual harassment, should share their internal guidelines on combating sexual harassment in their University with other Universities across India. As an example, the internal complaint committee of JNU is known as Gender Sensitisation Committee against Sexual Harassment, which is stated to have been extremely effective in its working partly due to the diverse nature of its constituent members. This model may be examined. [page 140]

In January 2014, a notification from the registrar of the University of Delhi (DU) declared that the Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, Redressal) Act, 2013 ‘supersedes’ University Ordinance XV-D (Prohibition of and Punishment for Sexual Harassment). I do not want to find any similarity in the DU declaration and the GSCASH replacement notification other than a practice of what may be called a ‘culture of notification’, going completely against the democratic spirit and process through which both these committees had come into being and functioned.

Lessons from Ambedkar University

Delhi’s Ambedkar University (AUD) also had a gender issues committee since its inception in 2008, in which I was a (co-opted) member from 2012. Members of this committee anchored the process to discuss the need for a formal institutional structure – in the lines of GSCASH – to deal with sensitisation, prevention and redressal of sexual harassment. It undertook widespread consultations with members who had served in JNU and DU committees, lawyers who would assist in the formulation of these rules and procedures and read through policies of JNU, DU, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, and National Law University, Bangalore. Our task was to look at the existing policies, take the best from them, try and retain the guiding principles of the 2013 Act, without compromising on the ideology of the Vishaka judgment. Through a number of iterative processes involving the faculty, students external experts and members of the Academic Council of the university, the board of management, in April 2014, adopted the policy on ‘Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal of Sexual Harassment and Discrimination on the basis of Gender Identity and Sexual orientation’. The Committee for the Prevention of Sexual Harassment (CPSH) was subsequently established. It is an entirely elected body with representations from the faculty, students, non-teaching staff, hostel residents, research scholars and external members (from a panel of ten experts). It can invite members from Ehsaas, the university clinic for psychotherapeutic services, if necessary.

Since the CPSH was established after many legal processes elsewhere and real experiences of the challenges that committees like this has encountered, it could benefit from both. There were at least three important shifts marking the CPSH: a) bringing sexual orientation within the policy as a probable basis of sexual harassment, b) making any person, belonging to any gender, lodge a complaint of sexual harassment and c) integrating counselling and therapy within the structure.

Ambedkar University, Delhi. Credit: AUD

It is only through the CPSH that AUD had the first taste of an election in its campus. In the election, campaigns were conducted and parchas were distributed around the politics of sexuality, emphasising that talking about sexual harassment was not only talking about violence, but also about what is undesirable/unwelcome. In 2015, the first elected committee started functioning.

The AUD process of instituting a committee was extremely participatory. Continuous efforts towards sensitising different segments of the university community are still made. The formation of committees like the CPSH or GSCASH is not an end in itself, rather, it is also the beginning of another journey – sustaining an environment of dialogue rather than discipline, enabling rather than constraining, preventive and not punitive, transparent (with anonymity) and not secretive (with procedural delays). Committees like these are a product of years of women’s movements, feminist pedadogies and practices within and outside university spaces. They are now mandatory within higher educational institutions, but cannot merely be a UGC-mandated and authority-nominated team that erases the history through which they came into being.

Hok Kolorob (let there be clamour) – mahila mange azaadi

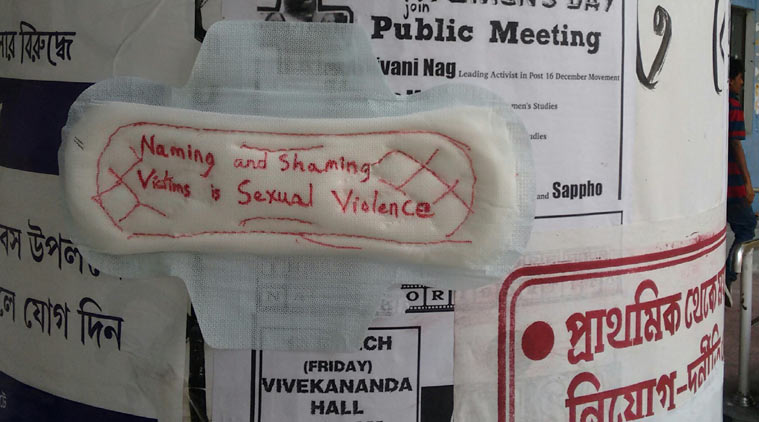

Universities are a site of possibilities and contradictions. They foster ideas and imaginations of new citizenship by removing boundaries of who can have access to higher education. On the other hand, universities also cultivate power in relationships while encouraging and sustaining relations – all of which are a complex web of multiple social locations and identities that individuals inhabit based on gender-sexuality, caste, class, religion, language, disability or place of origin. I shift towards incidents of sexual harassment happening in campuses, and being protested by students across campuses because there is a necessary corollary to be established between these protesting voices and the processes that are underway to curb them. August and September 2014 saw a new slogan from young college-going people – hok kolorob – which started from the streets of Kolkata, as a response to a problematic handling of a reported case of sexual harassment at Jadavpur University (JU) and against the subsequent police attack on peacefully agitating students. This development led to the emergence of new campaigns in the university. In March 2015, JU women students aligned with the broader #padsagainstsexism protests initiated by a few students in Jamia Milia Islamia, New Delhi. I fondly remember that one of the first student collectivising initiatives that had taken place at AUD was keeping sanitary napkins in a table in front of the university library and classroom blocks. At nearly the same time as the protest in JU, another incident of sexual harassment against a woman student at Visva Bharati, Shantiniketan, was reported. After much interrogation and humiliation faced faced by the complainant and her father, she had to eventually quit her academic life. Students at the campus protested the manner in which this incident was handled by the authorities. Yet another incident of sexual harassment at Banaras Hindu University (BHU) was reported on September 23, which prompted protests by students. It brought out in the open that while women students are mostly silenced by the authorities, at times, they do decide to organise themselves to make kolorob, loud and clear.

A woman student at BHU was reported as saying,”[t]he boys are free to roam on the campus through the night, with lax curfew timings. But we are closely watched, our entry timings are noted in a register and we are thoroughly questioned even for a delay of a few minutes,” while another said, “They want to silence us and tame us. This protest has become a marker. It is the biggest women’s protest in the 100-year history of the BHU. And it was waiting to happen”.

#padsagainstsexism protests were initiated by a few students in Jamia Milia Islamia. Credit: Twitter

Is it that in this kolorob towards azaadi lies the threat to monogamous hetero-patriarchy that universities also represent and preserve as a culture? There is a new language in which college-going students across various Indian cities are protesting since the 2012 Delhi gang rape. That language claims freedom from both baap and khap, makes proclamation over one’s body and sexual autonomy while also screaming ‘pinjra tod‘. These feminist voices – aloud and abound – democratising public and private spaces and spaces at the cusp of these (like the hostel or the paying guest accommodations) have marked their entry in the broader political environment. The threat this poses to the monogamous hetero-patriarchy prompted the BHU vice chancellor to warn girl students against talking about sexual harassment – after all, in openly talking about sexual harassment, the girl students “have put their modesty in the market“!

Talking about ‘sexual politics’

It is important to note this transforming landscape in which young, aspiring, freedom-seeking women in institutions of higher learning across Indian cities talk about, discuss and debate sexual politics. A democratically-elected anti-sexual harassment body needs to recognise, reflect, co-create and incubate this new politics. The GSCASH was never meant to be only a complaint registering body; it was always supposed to ‘sensitise’, generate dialogue among all constituencies of the university on how gender intersects and interplays with all other social and cultural locations and identities to make it a complex political category.

Although as per the UGC 2015 notification, higher educational institutions have the responsibility to create awareness on sexual harassment and what constitutes a hostile environment, yet a nominated ICC with a very narrow mandate of just making an enquiry only on the written complaints, absolves it from taking responsibility of the sensitisation. It does not make any separate body in the university responsible for conducting these sensitisation initiatives regularly, thereby promoting negligence of the most important aspect of the Vishaka judgement – preventive measures to a sexually violent environment. On the one hand, there is a changing language of feminist politics in contemporary India and on the other hand, a top-down non-democratic propaganda of constituting anti-sexual harassment committees. I see a connection between the two – the more we talk of desire, intimacy and embrace besharmi, the more will be the need to silence us. There is a way in which political freedom is being articulated through challenging gender-sexuality hierarchies and there lies the importance of these times when young people (of many gender identities) across Indian cities are taking risks to defy the culture of silence.

It is also important to underlie that in this changed environment of adult consensual sexual relationships, all democratically-elected GSCASH-like committees need to be sensitive towards a more responsive commitment to sexual infringements while encouraging greater dialogue among younger people. JNU, as a space, gave and still gives the first taste of freedom and dissent of various kinds to many of its students, which is what any university ideally needs to provide. With this autonomy comes a commitment towards being just to multiple kinds of transformations that life in a campus creates.

I end with an excerpt from the Verma committee report:

[t]he time has come when women must be able to feel liberated and emancipated from what could be fundamentally oppressive conditions against which an autonomous choice of freedom can be exercised and made available by women. Thus, we notice the guaranteeing of the private space to the women, which is to choose her religious and private beliefs and also her capacity to assert equality which is in the public space is vitally important. Very often, a woman may have to assert equality vis-à-vis her own family and that is why it is necessary to understand the subtle dimension of a woman being able to exercise autonomy and free will at all points of time in the same way a man can. This, we will later see, is sexual autonomy in the fullest degree [page 139].

There is a greater threat to monogamous hetero-patriarchal politics in creating an enabling condition for this sexual and political autonomy for women and all queer people. There lies the potential and the possibility of (sexual) politics in campuses and coming into the streets outside the institutions of higher learning. The need for elected bodies like the GSCASH or the CPSH is supreme for promoting a certain spirit of contemporary feminist politics. It is important to ensure they do not become dogmatic structures instituting surveillance and preventing dialogue.

Rukmini Sen is associate professor at the School of Liberal Studies, Ambedkar University, Delhi.