Pick up Gulliver’s Travels expecting a children’s book or a novel and you will be unpleasantly surprised. Originally published as Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts … By Lemuel Gulliver, first a Surgeon, and then a Captain of several Ships, it is one of the great satires in world literature.

Jonathan Swift by Francis Bindon. Swift is pointing to Part IV of the Travels, Voyage to the Country of the Houyhnhnms. Note the horses in the background. Credit: Wikimedia

First published in London in 1726, the Travels was a sensational bestseller and immediately recognised as a literary classic. The author of the pseudonymous Travels was the Church-of-Ireland Dean of St. Patrick’s in Dublin, Jonathan Swift. Swift wrote that his satiric project in the Travels was built upon a “great foundation of Misanthropy” and that his intention was “to vex the world”, not entertain it.

The work’s inventive narrative, exuberant fantasy (little people, giants, a flying island, spirits of the dead, senile immortals, talking horses and odious humanoids), and hilarious humour certainly made the work entertaining. In its abridged and reader-friendly form, sanitised of sarcasm and black humour, Gulliver’s Travels has become a children’s classic. In its unabridged form, however, it still has the power to vex readers.

What’s it all about?

In Part 1 of this four-part satire, Gulliver is shipwrecked among the tiny Lilliputians. He finds a society that has fallen into corruption from admirable original institutions through “the degenerate Nature of Man”. Lilliput is a satiric diminution of Gulliver’s Britain in its corrupt court, contemptible party politics, and absurd wars.

In Part II Gulliver is abandoned in Brobdingnag, a land of giants. The scale is now reversed. Gulliver is a Lilliputian among giants, displayed as a freak of nature and kept as a pet. Gulliver’s account of his country and its history to the King of Brobdingnag leads the wise giant to denounce Gulliver’s countrymen and women as “the most pernicious Race of little odious Vermin that Nature ever suffered to crawl upon the Surface of the Earth”.

In Part III Gulliver is the victim of piracy and cast away. He is taken up to the flying island of Laputa. Its monarch and court are literally aloof from the people it rules on the continent below, and absorbed in pure science and abstraction.

Technological changes originating in this volatile “Airy Region” result in the economic ruin of the people below and of traditional ways of life. The satire recommends the example of the disaffected Lord Munodi, who is “not of an enterprising Spirit”, and is “content to go on in the old Forms” and live “without Innovation”. Part III is episodic and miscellaneous in character as Swift satirises various intellectual follies and corruptions. It offers a mortifying image of human degeneration in the immortal Struldbruggs. Gulliver’s desire for long life abates after he witnesses the endless decrepitude of these people.

Part IV is a disturbing fable. After a conspiracy of his crew against him, Gulliver is abandoned on an island inhabited by rational civilised horses, the Houyhnhnms, and unruly brutal humanoids, the Yahoos. Gulliver and humankind are identified with the Yahoos. The horses debate “Whether the Yahoos should be exterminated from the Face of the Earth”. As in the story of the flood in the Bible, the Yahoos deserve their fate.

Gulliver taking his final leave of the land of the Houyhnhnms. Sawrey Gilpin, 1769. Credit: Wikimedia

The horses, on the other hand, are the satire’s ideal of a rational society. Houyhnhnmland is a caste society practicing eugenics. Swift’s equine utopians have a flourishing oral culture but there are no books. There is education of both sexes. They have no money and little technology (they do not have the wheel). They are authoritarian (there is no dissent or difference of opinion). The Houyhnhnms are pacifist, communistic, agrarian and self-sufficient, civil, vegetarian and nudist. They are austere but do have passions. They hate the Yahoos.

Convinced that he has found the enlightened good life, free of all the human turpitude recorded in the Travels, Gulliver becomes a Houyhnhnm acolyte and proselyte. But this utopian place is emphatically not for humans. Gulliver is deported as an alien Yahoo and a security risk.

Wearing clothes and sailing in a canoe made from the skins of the humanoid Yahoos, Gulliver arrives in Western Australia, where he is attacked by Aboriginal people and eventually, unwillingly, rescued and returned home to live, alienated, among English Yahoos. (Swift’s knowledge of the Aboriginal people derives from the voyager William Dampier, whom Gulliver claimed was his “Cousin”.)

Politics and misanthropy

When it was published, the Travels’ uncompromising, misanthropic satiric anatomy of the human condition seemed to border on blasphemy. The political satire was scandalous, venting what Swift called his “principle of hatred to all succeeding Measures and Ministryes” in Britain and Ireland since the collapse, in 1714, of Queen Anne’s Tory government, which he had served as propagandist.

In its politics the work is pacifist, condemns “Party and Faction” in the body politic, and denounces colonialism as plunder, lust, enslavement, and murder on a global scale. It satirises monarchical despotism yet displays little faith in parliaments. In Part III we get a short view of a representative modern parliament: “a Knot of Pedlars, Pickpockets, Highwaymen and Bullies”.

Gulliver’s Travels belongs to a tradition of satiric and utopian imaginary voyages that includes works by Lucian, Rabelais, and Thomas More. Swift hijacked the form of the popular contemporary voyage book as the vehicle for his satire, though the work combines genres, containing utopian and dystopian fiction, satire, history, science fiction, dialogues of the dead, fable, as well as parody of the travel book and the Robinson Crusoe-style novel.

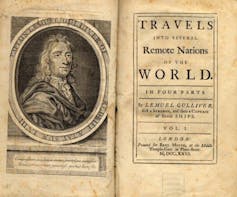

The frontispiece and title page of the first edition of Gulliver’s Travels (1726). Credit: Wikimedia

It’s not a book to be judged by its cover. The frontispiece, title page and table of contents of the original edition gave no hint that this was not a genuine travel account. Swift and his friends reported stories of gullible readers who took this hoax travel book for the real thing.

It is also not reader friendly. The revised 1735 edition of the Travels opens with a disturbing letter from Gulliver in which the reader is arraigned by an irate and misanthropic author convinced that the “human Species” is too depraved to be saved, as evidenced by the fact that his book has had no reforming effect on the world. The book ends with Gulliver, a proud, ranting recluse, preferring his horses to humans, and warning any English Yahoos with the vice of pride not to “presume to appear in my Sight”.

Readers might dismiss the unbalanced Gulliver, but he is only saying what Swift’s uncompromising satire insists is the truth about humankind.

![]() In many ways Jonathan Swift is remote from us, but his satire still matters, and Gulliver’s Travels continues to vex and entertain today.

In many ways Jonathan Swift is remote from us, but his satire still matters, and Gulliver’s Travels continues to vex and entertain today.

Ian Higgins, Reader in English, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.