While the first half of 1968 was a series of explosive moments – the Tet Offensive, Paris protests, the assassinations of MLK and RFK, the Chicago Democratic National Convention riots – the second half seemed like a car wreck in slow motion.

The pace of the news cycle slowed to a crawl, the shock and surprise followed by the dull inevitability of events already set into motion.

The music of 1968 mirrored its historical moment.

The trends and styles of the previous year – the psychedelic rock born of the Summer of Love, the empowerment of Aretha Franklin’s demand for “Respect,” a rainbow coalition of black and white artists collaborating – passed into instant obsolescence, creating a vacuum waiting to be filled.

The three pillars of 1960s pop music – Bob Dylan, the Beatles and the Motown hit machine – certainly didn’t rise to the occasion. Each put out music that was adrift and directionless, and each would lose its momentum and see its influence wane.

Drifter’s escape

In the last days of 1967, Bob Dylan quietly released “John Wesley Harding.”

The prior year, Dylan had been in a motorcycle accident, and his condition was shrouded in mystery. An 18-month period of silence followed, during which Dylan wrote and recorded “John Wesley Harding” with a trio of Nashville musicians.

But the long-awaited album contained none of the piercing anger, wit or wordplay of his white-hot classics “Bringing It All Back Home,” “Highway 61 Revisted” and the 1966 double-album set “Blonde On Blonde.”

“John Wesley Harding” lacked the incisive social commentary of tracks like “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (“You don’t need a weatherman / To know which way the wind blows”) or the razor sharp character studies found in songs such as “Like a Rolling Stone” (“Nobody’s ever taught you how to live out on the street / And now you’re gonna have to get used to it”).

Instead, Dylan wove perplexing parables couched in biblical imagery in songs such as “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” and “All Along the Watchtower,” in which he sang, “Outside in the cold distance, a wild cat did growl. Two riders were approaching; the wind began to howl.”

The album’s darkly mysterious nature set an ominous tone for the year to come.

The forlorn four

Like Dylan, the Beatles seemed to be in the midst of an existential crisis.

Following the death of their manager, Brian Epstein, in 1967, the Beatles headed to India, where they studied transcendental meditation with Indian guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. When they reconvened in London a few months later, they were no longer bright-eyed youths but four disillusioned men seeking answers and finding none.

Also read: The First Encounter Between Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and The Beatles

After the tumultuous events of the first half of 1968, the group returned to the airwaves with an anthem to the power of positive thinking.

Released in September of that year, the single “Hey Jude” sat atop the charts for months. The song’s first half urged the listener to take a sad song and make it better, while the second half – four minutes of nonsense chanting, slowly fading into infinity – offered only the notion that “though we may be lost, we are all lost together,” a hymn for a community that defined itself more by grief and resignation than by a belief in a better future.

Also read: The Beatles and Me: In the Maharishi’s Ashram, 50 Years Ago

The double album that followed in late November – officially titled “The Beatles,” but forever referred to as the “White Album” – brought together splintered fragments of the group’s experiences. It contained none of the audacious discovery and very little of the exuberance found in their previous work.

The track “Revolution #1” was the Beatles’ most direct engagement with the politics of the moment. But it was decidedly ambivalent, arriving at the muddled confusion of “count me out in.” It seemed to urge the listener to take up arms, even as the lyrics urged acceptance: “Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright.”

The widening racial divide

In the mid-1960s, Detroit’s Motown Records had issued a string of singles that rivaled the Beatles for chart supremacy.

But with Detroit in flames during the riots of 1967, the label lost its mojo: The upbeat cheer of the Motown sound was at odds with the violence erupting just a few blocks from the studio.

In 1968, the label’s two biggest acts – The Temptations and The Supremes – barely managed to make the charts, and the few releases that did were dim shadows of earlier brilliance.

The events of 1968 would even more directly effect Stax records, Motown’s biggest rival.

Based in Memphis, Tennessee, Stax artists like Otis Redding and Sam and Dave proudly wore their rough edges and black identity, unlike the polished acts Motown fashioned for The Ed Sullivan Show.

Redding, however, died in a plane crash in December 1967 – an ominous portent for the new year.

On the night of Dr. King’s assassination, just a few blocks from the Stax offices and studio, its legendary integrated house band, Booker T and the MGs, came face-to-face with the racial divisions their very existence had defied.

Fearing for the lives of the two white members, the musicians and staff formed a caravan to escort them safely out of a neighborhood soon engulfed in flames. Though the band continued to work together for another year, the bubble had burst: A community fell apart, and the hits dried up.

James Brown was one of the first stars to directly address the year’s racial tumult in his music, issuing “Say it Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” in the late summer of 1968.

For a moment, he would bridge the gap between black and white, soul and pop, famously holding Boston together with a concert performed the day after King’s assassination.

This night, however, would prove the high water mark for Brown, whose increasingly political music caused him to lose much of his white audience, relegating him to the niche of soul music.

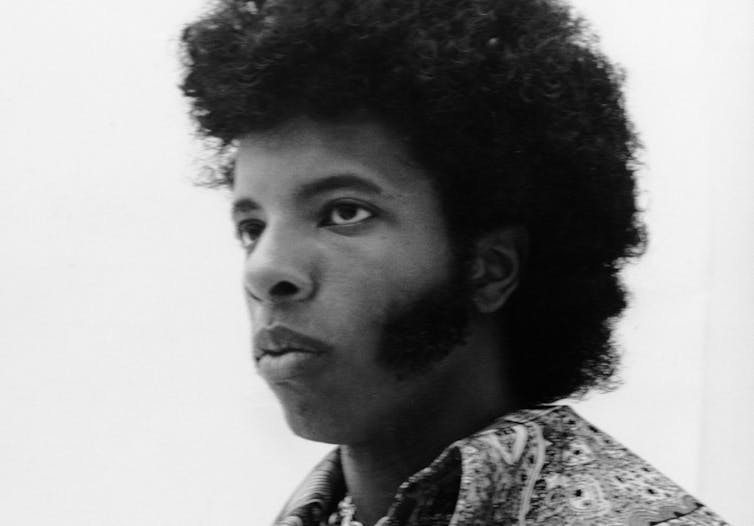

Sly Stone met a similar fate. His 1968 breakout hit, “Dance to the Music,” featured a multiracial band of men and women, creating a musical rainbow coalition.

In the 1970s, Sly Stone seemed to succumb to cynicism.

But within a year, Sly’s message became considerably less rosy. His 1969 album “Stand!” contained the song “Don’t Call Me Nigger, (Whitey)” while his 1971 follow-up, “There’s a Riot Going On,” depicted a dystopian view of the future. Like Brown, he would fade from the mainstream.

After the hopeful days of Swinging London and the Summer of Love, the events of 1968 triggered classic fight or flight responses.

A few musicians metaphorically took to the streets.

But most fled for cover, going back to the land or looking to God.

Compared to the more radically charged music of 1969, the resigned hymns of 1970, and the escapist fare that dominated the following decades, 1968 serves as a kind of still point, an extended moment of hesitation after a gunshot, just before the fight-or-flight reflex kicks in.![]()

Alan Williams, Chair of Music Department, University of Massachusetts Lowell.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.