Loving Vincent isn’t hagiography but deep sincere reverence, attempting to understand and celebrate one of the finest minds of the 19th century, one that sadly gained prominence only posthumously.

Vincent van Gogh, an iconic figure in the art world, was a deeply lonely man, perpetually beset with mental demons. His joy, despair and sorrow found expression in not just oil paintings but also letters, most of them addressed to his younger brother, Theo, an abiding influence in van Gogh’s life. Van Gogh’s letters, considered fine pieces of literature, typically ended with the phrase, “Loving Vincent”.

The title of Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s feature film, Loving Vincent, examining van Gogh’s life and death, playing at the 19th Mumbai Film Festival, seems at cursory glance an acknowledgement of his signature. But on closer inspection, “Loving Vincent” acquires a more poignant meaning: of the filmmakers and artists – 115 painters – paying their respects to a master, someone whose life and work they are enchanted by, enamoured with.

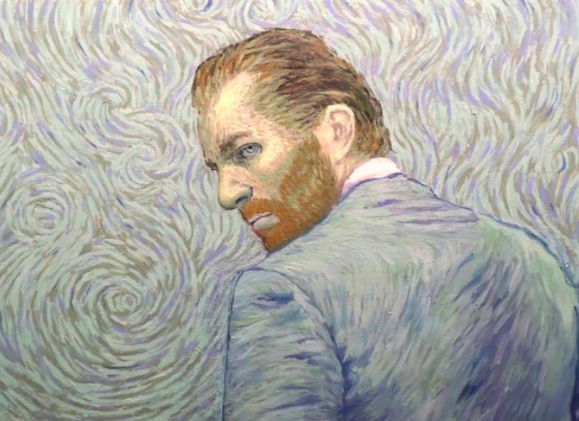

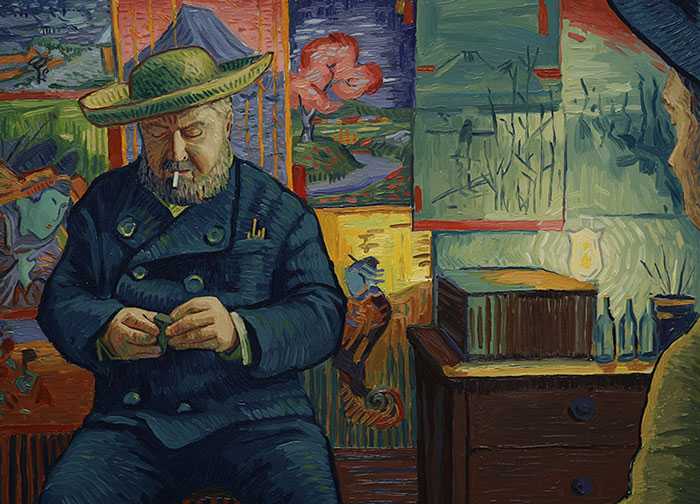

Van Gogh permeates every frame of Loving Vincent. He features not just in the film’s story but also in its language. Loving Vincent is a result of animating 62,450 oil paintings on canvas, inspired by van Gogh’s style, that attempts to reach an artist through his art. Here, the content doesn’t just decide the form; it also becomes the form. This stylistic choice is befitting because if it is difficult to separate art from an artist, then the biopic of an artist shouldn’t be separated from his art either. Loving Vincent considers that line of thought seriously, taking it to a powerful satisfying conclusion.

Unfolding in 1891, a year after his death, Loving Vincent begins with postman Joseph Roulin telling his son Armand to deliver van Gogh’s letter to Theo. Blending fact and fiction (Joseph and Armand are characters in van Gogh’s pictorial world), this animated biographical drama adopts a unique approach to depict and deconstruct an artist’s life. Unnatural death, especially if its cause is either murder or suicide, becomes more intriguing than life itself. It’s a question that haunts and occupies Loving Vincent too: Why did van Gogh die? He is widely believed to have shot himself in the chest, at the age of 37, dying 30 hours after the incident. But the film contests that claim more than once. It’s as if the filmmakers can’t bear the thought of van Gogh losing out to life. Even more than a century later, his death refuses to provide clear answers. There’s only swirling gossip and unending speculations.

But Loving Vincent goes further. It presents different perceptions of the van Gogh story, prodding us to arrive at our own answers, casting light on the questions typically raised by the death of an illustrious artist. Kobiela and Welchman devise an impressive structure to tell this story. The film alternates between the present, Armand talking to key figures in van Gogh’s life (his physician, Dr Gachet; his alleged love interest, Marguerite; Adeline Ravoux, the owner of a family home where he died) and the past, them recounting his childhood, his love for painting, his struggles with mental health. These accounts help us understand van Gogh better, placing his story in the stories of other tortured geniuses. It has shades of Franz Kafka’s childhood: a boy trying hard to please his parents. It has shades of David Foster Wallace’s final days: a man trying hard to come out of his own mind. In doing so, Loving Vincent paints a heartfelt portrait of an artist’s journey, of a late bloomer, who took to painting at the age of 28, ironically stopping at an incipient stage of his career – his unparalleled mastery making sure that even that short duration was worth a lifetime of work.

Loving Vincent has smart narrative chops, but that alone wouldn’t have made it memorable. It becomes so by following van Gogh’s footsteps, adapting his story by embracing his style. Many scenes reference his work, such as Bedroom in Arles, The Night Café and Still Life with Glass of Absinthe and a Carafe, offering insight into his real and painted worlds. This isn’t hagiography but deep sincere reverence, attempting to both understand and celebrate one of the finest minds of the 19th century, one that sadly gained posthumous prominence. Moreover, the animated paintings render even the most mundane frames – leaves fluttering on streets, windows swinging open, coffee pouring into cups – lyrical, much like van Gogh’s body of work.

Informed by art, humour, speculations and accusations, Loving Vincent is a smart blend. It is also a deeply sad story, of a life cut woefully short, of its admirers not finding closure, of an artist unable to understand his own worth, of him not recognising that the night is not just dark and lonely and deep but also lit with sea of stars.

Loving Vincent will be screened at PVR Juhu on October 15 (1:55 pm) and Regal on October 18 (7:15 pm).

Comments are closed.