Excerpted with permission from Calcutta Then | Kolkata Now.

‘The history of Colonial Calcutta dates from August 24, 1690,’ says P. Thankappan Nair, the city’s dedicated chronicler. That was when the East India Company’s Job Charnock slipped anchor in the Hooghly. Nine years later he paid Rs 1,300 to the Savarna Raychaudhuri family of Barisha for zamindari rights over the three villages of Kalikatah, Sutanati and Govindpur. The town had a bad press from the beginning. Robert Clive thought Calcutta ‘the most wicked place in the universe’. Mark Twain complained after only two days that the climate was ‘enough to make the brass doorknob mushy.’ Rudyard Kipling called it the ‘city of dreadful night.’ The mythic horrors of ‘the Black Hole of Calcutta’ of British imagination became the metaphor for the city until Saint Teresa, the Albanian-born Roman Catholic missionary, replaced it with an even more horrific image of death and disease.

There was compensation for braving this fearsome reputation. Kipling chanted,

Me the Sea-captain loved, the River built,

Wealth sought and Kings adventured life to hold.

Hail, England! I am Asia—Power on silt,

Death in my hands, but Gold!

Sunanda K. Datta-Ray and Pramod Kapoor

Calcutta Then | Kolkata Now

Roli Books, 2018

Although the profit motive created Calcutta, European officials playing at being gentlemen dismissed European businessmen as boxwallahs or itinerant pedlars. Even the Scots Sir David Yule, who headed the biggest British conglomerate, Andrew Yule and Company, market leaders in jute, tea and river shipping, couldn’t escape the taint of trade. The official sahibs didn’t think him good enough to meet King George V who visited Calcutta in December 1911. The king sent for him nevertheless and the two men got on so famously that their meeting, scheduled for thirty minutes, extended for an hour. Office lore had it, recalled Bhaskar Mitter, who became Andrew Yule’s chairman in 1968, that His Majesty was mightily impressed when crossing the jetty to a jute mill, the thrifty Scotsman bent down and picked up a strand of the silvery fibre. His staff was warned not to waste the precious raw material.

Indians were never similarly supercilious about boxwallahs. Sir David’s uncle and the company’s founder, George Yule, was invited to preside over the Indian National Congress in 1888, the first non-Indian in the chair. Trade was Calcutta’s lifeblood. Many of the grandest families descended from the banians or agents of empire-builders like Charnock, Clive and Warren Hastings. They became formidable traders on their own account and rebutted the popular charge that Bengalis make poor businessmen.

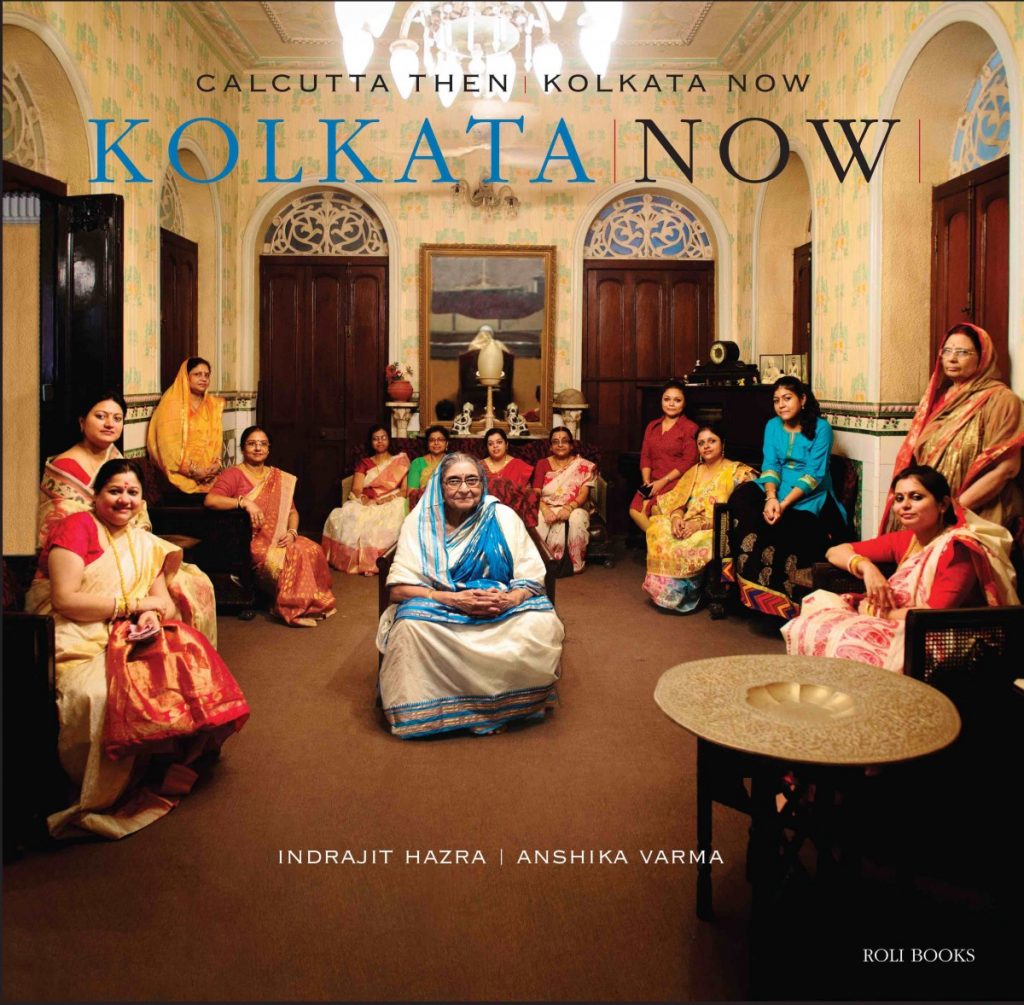

Indrajit Hazra and Anshika Varma

Calcutta Then | Kolkata Now

Roli Books, 2018

‘If you see a pillared palace in north Calcutta,’ says Dr Somendra Chandra Nandy, scholarly heir to the princely Cossimbazar family’s thriving china clay business, ‘the chances are the founder was a salt trader!’ His own ancestor, Maharaja Krishna Kanta Nandy (known as Cantoo Baboo), Hastings’ banian, began with buying the fruit of a jackfruit tree in 1742 when he was only twenty-two. Trading in salt, silk and zamindari made him so rich that Edmund Burke thundered in the House of Commons in 1783 that Cantoo Baboo earned an annual £140,000 in rents alone.

The highly cultured Tagores were also businessmen. The first prominent Tagore was a stevedore. His grandson was a moneylender. Dwarkanath, poet Rabindranath’s grandfather, styled ‘Prince’ by the British because of his lavish lifestyle, was into salt and shipping. The shipowner, Ramdulal Dey (1752-1825), the first Calcutta merchant with overseas links, lent money to American traders.

Money didn’t always buy taste but it enabled banians to patronize the arts and indulge in philanthropy. Marble Palace, the most spectacular of the ‘pillared palaces’, built in 1835 by Raja Rajendra Mullick Bahadur, is a neoclassical fantasy carved from ninety different kinds of marble from all over the world, crammed with statues and chandeliers, paintings, weapons, china, crystal, mirrors and clocks. The Mullicks were bullion merchants. Their family trust still feeds five hundred poor people daily. Like the Savarna Raychaudhuris, Tagores, Cossimbazars and other grand families, the Mullicks also celebrate Durga Puja, the Mother Goddess’ brief return to her parental home, with great fanfare every October for all comers.

The Lieutenant-Governors of Bengal’s official residence. Credit: British Library

Credit: Getty Images

Credit: Clyde Waddell/Upenn Ms. Coll

Credit: Private Collection

Credit: Zentralbibliothek Zurich