It’s the perfect time to read Proust. That’s what I thought at the beginning of the lockdown. At the end of the year, I haven’t managed even the first page of his Remembrance of Things Past.

It wasn’t just Proust. The pandemic provided privileged time to read, but took away the focus. The Booker Prize winner, the presidential memoir, the final instalment of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy: all these and more gather dust on the to-be-read pile.

Nevertheless, I did manage to get some reading done when I wasn’t doomscrolling, attending Zoom meetings, or refreshing coronavirus updates. Here, in no particular order, is a baker’s dozen of the fiction and non-fiction published in 2020 that I found noteworthy.

Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar

Akhtar mines his own life to come up with a remarkable novel of race, class and ambition in today’s America. It’s a collection of set pieces tied together by the narrator’s relationship with his father, an immigrant from Pakistan. There are echoes of Philip Roth in the supple, probing sentences, and shadows of Whitman in his songs of the country’s unities and fractures.

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line by Deepa Annapara

This debut novel set in an Indian slum has a density of lived detail and a distinctive voice that raises it above similar work. At the start, it’s about a nine-year-old’s search for a missing classmate; by the end, it manages to portray life near the bottom of an inequitable social structure, with threats of demolition, corrupt policemen, and the consolations of religion.

Hellfire by Leesa Gazi (translated by Shabnam Nadiya)

The word “searing” is often used to describe novels. In this case, it’s justified. Structured around the haunted central character’s trip to Dhaka’s Gausia Market on her fortieth birthday, Hellfire is a stark and compelling evocation of how the need to keep a tight check by a family – or a society – can unravel in the course of a single day.

Square Haunting by Francesca Wade

Mecklenburgh Square is a quiet enclave at the edge of London’s Bloomsbury. Between the world wars, it was home to five women writers whose stories intertwine in this book: poet Hilda Dolittle, novelist Dorothy Sayers, classicist Jane Harrison, economic historian Eileen Power, and author Virginia Woolf. With delicacy and insight, Wade outlines their search for creative freedom at a time of transition. These stories “bring the brick and asphalt to life, and bind the present to the past”.

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli (translated by Elisabeth Jaquette)

There’s a spare, Coetzee-like quality to this novel about the haunting continuity of loss. The narrator is obsessed by a minor detail that surrounds the capture and rape of a young Palestinian woman by Israeli forces in 1949. Decades, later, she sets out to investigate and find closure. It would be easy to let indignation and rage overpower the telling, but Shibli’s strategy is more potent: she uses a measured, impassive style that gets under the skin.

Twilight of Democracy by Anne Applebaum

This non-fiction chronicle of the role of writers, journalists, and activists in authoritarian regimes begins with a 1999 New Year’s Eve party thrown by Applebaum and her husband in Poland. She traces how many friends and associates who attended moved further right over the years, from supporting despotic rule to promoting conspiracy theories. It’s focused on Europe and America, but there are clear lessons for the rest of the world. Forewarned is forearmed.

Eat the Buddha by Barbara Demick

What is it like to be a Tibetan at the edge of modern China in the twenty-first century? That’s what Demick explores in this work of oral history stitched together from the recollections of people from remote Ngaba, the “world capital of self-immolations”. With empathy and skill, she portrays a people trying to resist cultural and political onslaught. A window into why so many are “willing to destroy their bodies by one of the most horrific methods imaginable”.

Welcome to the New World by Jake Halpern and Michael Sloan

This graphic novel has its roots in the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times comic strip about a Syrian refugee family’s true-life experiences after they arrive in Connecticut on the day that Trump wins the presidency. In affecting and unassuming panels, it reveals what they leave behind, what they gain, and what they undergo to create a new life for themselves.

Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu

Discovering a unique voice is one of the pleasures of reading a novel, not to mention finding one that plays with form. Both are present in Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown. It’s crafted as a screenplay in seven acts, featuring a Hollywood character trying to rise from Generic Asian Man to Kung Fu Guy. This account of a life on the margins moves from satire to insight, highlighting how the West views the rest.

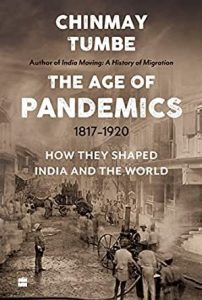

Age of Pandemics by Chinmay Tumbe

There’s a strong temptation to view the current pandemic as unique, calling for one-of-a-kind solutions. Chinmay Tumbe’s impressively-researched book provides a necessary long-term perspective by examining the impact of cholera, plague and influenza outbreaks from 1817 to 1920. India was at the centre of this mortality crisis, he writes, with deaths of over 40 million people. It’s full of details that now sound very familiar, from finger-pointing to dubious treatments to the successful development of vaccines.

The Bookseller’s Tale by Martin Latham; Burning the Books by Richard Ovenden; Dear Reader by Cathy Rentzenbrink

When reading books is hard, reading books about books can be the perfect antidote. This year, these three performed that role. Latham’s volume is loaded with literary anecdotes and trivia over the years. Ovenden focuses on libraries, from Mesopotamian to Alexandrian to Bodleian, and efforts to preserve information. And Rentzenbrink’s endearing memoir delves into the comforts of a lifetime passion for books. As Naomi Shihab Nye once observed: “It is really hard to be lonely very long in a world of words.”

Sanjay Sipahimalani is a Mumbai-based writer and reviewer.