In June 2018, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) sparked public outrage when its director Ish Kumar made a strong pitch for giving India’s police “limited access” to Aadhaar data for the purposes of investigating crime and tracing unidentified bodies.

This request, reportedly widely, was predictably met with a swift public denial by the Aadhaar authority, with the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) stating that Aadhaar data had never been shared with any crime investigating agency.

How credible is this denial, though? After all, there is evidence from as far back as 2013, before the enactment of the Aadhaar Act, to show that the police already had limited access to the Aadhaar database (often through court orders) and that the UIDAI had helped state police on a number of occasions.

In the last two years, there is more recent evidence to show how police departments across the country want to use Aadhaar. But before we get to that, it is important to understand why NCRB wants to access the Aadhaar database and how it would be able to do so.

Why does the NCRB need the UIDAI’s fingerprints?

India’s central fingerprint bureau is the nodal agency for setting standards, tools and processes for the collection, storage and analysis for fingerprints.

As fingerprint matching is considered crucial for nabbing repeat-offenders, standardisation of fingerprint images and allowing officials to search through them using an automated fingerprint identity system (AFIS) is important. The bureau’s 2015 report traces the trend towards automated searches and less reliance on manual processes. As of 2015, it holds 28 lakh fingerprints of arrested and convicted persons.

What bothers the NCRB the most, however, are first-time offenders because their fingerprints are not available in the AFIS. This is where the UIDAI comes in, because these fingerprints are very likely to be available in the Aadhaar database, considering how big it is.

NCRB’s Ish Kumar explains it the best:

“There is need for access to Aadhaar data to police for the purpose of investigation. This is essential because 80% to 85% of the criminals every year are first-time offenders with no records [of them available] with the police. But they also leave their fingerprints while committing crime. There is need for limited access to Aadhaar, so that we can catch them.”

How would this work though? From the NCRB’s point of view, access to biometric data available in the Aadhaar database through a simultaneous search will likely work as shown in the diagram below.

For this type of simultaneous search to work seamlessly, the fingerprint capture image formats must match with the stored image formats and must be standardised across both organisations.

This was done by NCRB in 2013 and were published as shown below:

| Biometric captured | Explanation | Standard used |

| Finger image | The raw image of the fingerprints | ISO/IEC 19794-4 |

| Minutiae images | The patterns in every fingerprint that is used for comparison | ISO/IEC 19794-2 |

| Mug shots | Facial photographs used | ITL – 1- 2011 (JPEG) |

Crucially, the UIDAI has also used these same standards from its inception (Page 15, Section 9) for finger and minutiae images. The standardisation thus allows fingerprint capture by all existing devices used in Aadhaar authentication and enrollment.

Two types of search

The NCRB’s fingerprint bureau holds annual conferences, which almost always have discussions on Aadhaar because of the sheer possibilities that a potential integration would offer.

With the imminent roll out of facial authentication by UIDAI, and the presence of a large fingerprint database, NCRB believes, in theory at least, that it can tap into the Aadhaar database in order to identify potential suspects (their demographic details and Aadhaar number) if they have latent fingerprints and CCTV mugshots of the perpetrators.

The process by which law enforcement searches for a list of potential suspects is usually referred to as a ‘1:N search’, meaning given a mugshot and fingerprint, the system could provide many potential suspects and their Aadhaar numbers.

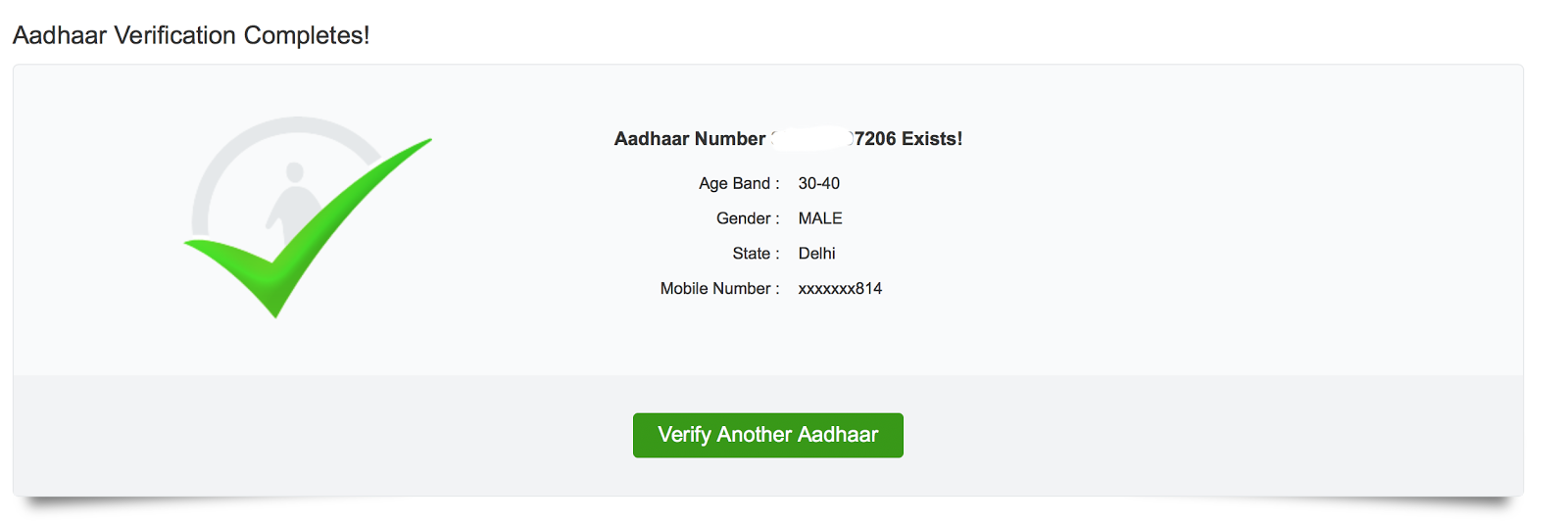

These Aadhaar numbers can then be used to query various databases to obtain a detailed profile of the potential suspects, which can then be used to further narrow down potential suspects (often referred to as ‘1:1 search’).

The NCRB’s interest to “limited access” to the Aadhaar database can be understood from the minutes of meeting available from each of its annual conferences.

- The 15th conference on 2013, was attended by the UIDAI deputy director general Ashok Dalwai, in which it was told that “UIDAI would eventually converge with the police department over time”.

- The 16th conference on 2014 requested access to UIDAI database for identification of dead bodies.

- The 17th conference (2015) requested amendments to the Identification of Prisoner Act, 1920 to add other biometrics. It reiterated the request to access UIDAI database for identification of dead bodies and also made the crucial observation that the removal of non-convicts post their acquittal from the fingerprint database must be prioritised.

- The 18th conference (2017) reiterated the amendment to the Identification of Prisoner Act and said, “Aadhaar may be linked to identify dead bodies”.

- The 19th conference, (2018) discussed the need to amend the Aadhaar Act and the Prisoner Act for “identifying first time offenders and also for identifying dead bodies”.

The 1:1 search

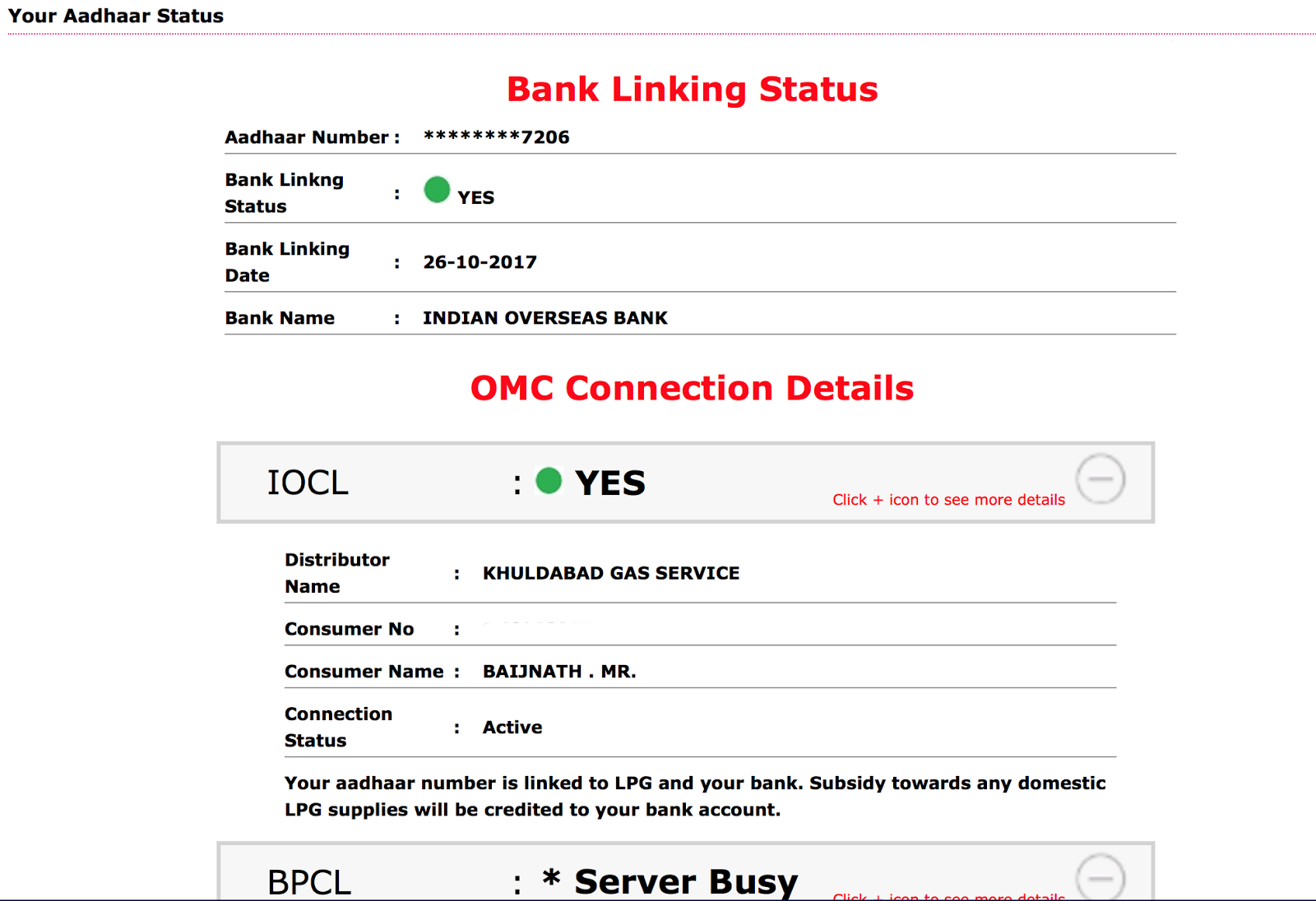

India’s state police departments do not have to depend upon the UIDAI at all when it comes 1:1 search. There are already various state and central databases which are seeded with Aadhaar numbers. Hence once the suspect’s Aadhaar number is known, the local enforcement agencies can simply ask the various public entities that own or operate these numerous databases to provide them with the required information.

For instance, India’s state police can merely ask local banks to provide all information associated with a particular Aadhaar number, including linked phone numbers.

This is how seeding Aadhaar numbers into various databases, referred to as “cross-seeding”, makes it easier to create 360-degree profiles, that are available on request for the law enforcement agencies without even needing a warrant.

Hidden backdoors for 1:1 search already exist

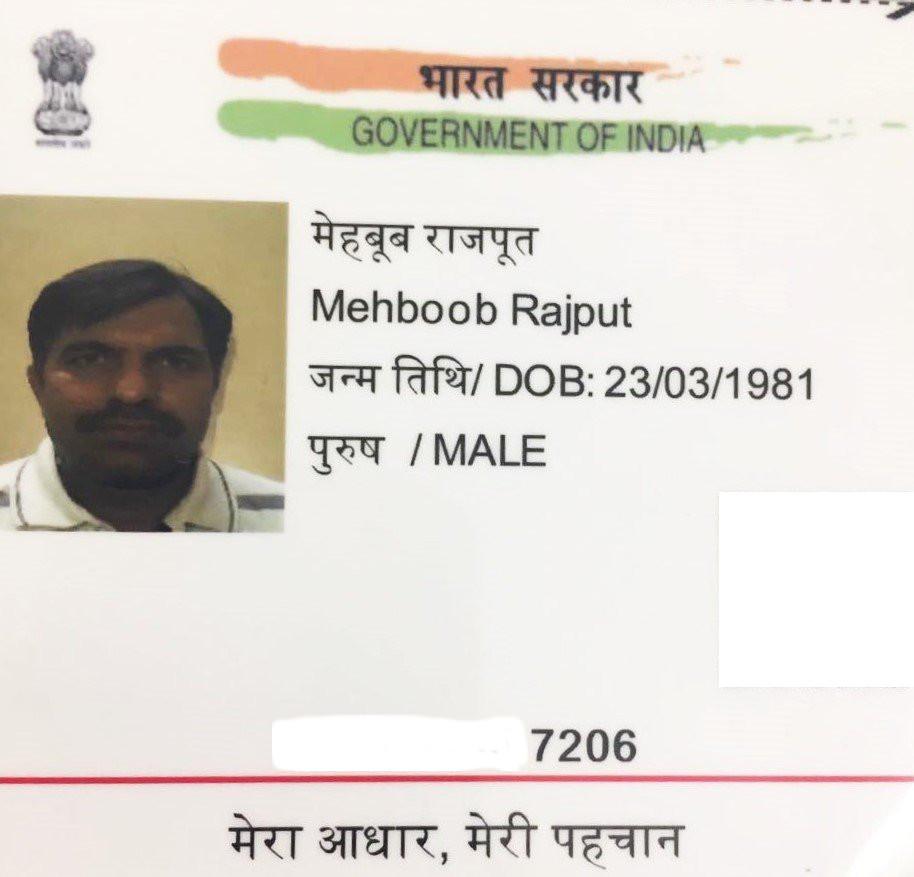

In October 30, 2017, the Times of India reported that a missing woman was identified from her half charred body using Aadhaar.

How could the police identify the woman from just a fingerprint? The back-door that allows this functionality is the “name/UID search” feature, which allows printing of an Aadhaar card, for those who have misplaced their Aadhaar number, using their fingerprints.

It is also obvious that a “fingerprint mould” was used by the police, since the woman was already dead. To know the identity of the missing woman, the police department obtained the names of all missing persons as reported in the district, during a specific time. It then used the “name search” feature along with their fingerprint mould to print their e-Aadhaar.

Screenshot of name/UIDAI feature. Credit: The Wire

Automating the 1:1 search

The southern state of Andhra Pradesh, has already created a vast fully interlinked resident database that has merged the crime and civilian aspects.

For instance the local state hub, has information about all its residents, the GPS coordinates of their homes, medicines they use, food rations they eat, what they say about their chief minister on their social media accounts, their caste, bank accounts on which they receive scholarships, pensions and their Aadhaar numbers.

This design allows the state police or any state official to know everything about an Aadhaar number holder by just typing their Aadhaar numbers.

A very similar exercise is under progress in the state of Telangana. The state hub hosts both the crime data and the Aadhaar data of the residents in one single entity called “Integrated Information Hub” and is also managed by the Hyderabad police.

Since the state police runs the state data hub, it also allows them full unlimited access to all the schemes that every family is enrolled into, along with access to authentication logs, thereby allowing real time tracking of the population, if need arises.

Telangana also offers an ongoing lesson on how a civil database (Aadhaar) and a crime database (used by NCRB and the various states) can converge. For instance, not only are the Aadhaar numbers of drunken drivers were seeded into the crime database, their family members’ Aadhaar numbers were also seeded.

Even those who are acquitted would continue to reside in the crime databases, and would be forced to share their Aadhaar numbers and their biometrics and also their family members’ details, until the courts directs them to stop doing so.

Purpose limitation is futile after a certain scale

Media reports over the last two years also indicate that the various crime databases maintained by the state and central bureaus are being cross-seeded with Aadhaar numbers and demographics, thereby converging the civilian and the crime database via a staged approach as described below:

- Madhya Pradesh police mull Aadhaar linking with the crime database.

- Home ministry directs prison authorities to link Aadhaar for tracking inmates and their visitors.

- Hyderabad police seek Aadhaar of those who are arrested, even before their conviction.

- Gwalior police seek Aadhaar of listed criminals in Madhya Pradesh.

- Tamil Nadu police demand Aadhaar from those who protest against bus fare hike.

- Rajasthan police plans to use Aadhaar for fetching data about suspects, victims and also complainants.

The cross-seeding of Aadhaar numbers with digital police systems such as the CCTNS (crime and criminal tracking network system) was something shunned by the initial team behind the biometric authentication programme.

“Nandan [Nilekani] told us that if they allowed us to do it, the people would never trust Aadhaar,” a former director-general of prisons of a large north Indian state told The Wire.

And yet, an early version of the software behind the Integrated Criminal Justice System (ICJS) – a programme that seeks to link the police’s criminal tracking system (CCTNS) with the digital information-technology systems for India’s courts and prisons – shows that Aadhaar was meant to serve as a crucial component of the overall ecosystem.

A screenshot of an initial version of how ICJS would look. Credit: The Wire

The image above is from 2016, showing that the NCRB, which implements the CCTNS and ICJS projects, had hoped to have the Aadhaar Act amended by now.

Parsing the UIDAI’s denial

The UIDAI in its denial asserted that “use of Aadhaar biometric data for criminal investigation is not allowed under the Aadhaar Act” and quoted Section 29 of the Aadhaar Act as corroboration.

The denial thus is limited to access to the biometric data (1:N search) and does not cover other cases like automated 1:1 access or request-based access to other entities. Furthermore, it also does not explicitly deny the creation of parallel biometric databases.

For instance, both the Hyderabad police (Entry 105) and the Chandigarh police (Entry 125) are on the list of Authentication User Agencies (AUA) and KYC User agencies (KUA) AUAs and KUAs are entities that are given access to the central Aadhaar database (CIDR) for authenticating Aadhaar holders.

This KUA access is sufficient for the police of both states to forcefully authenticate any arrestees to obtain their demographic information from the Aadhaar database.

Once KYC authentication fetches the demographic information, the police can use the Identification of Prisoners act, 1920 to obtain their fingerprints in the same standardised form used by the UIDAI to create a parallel database which mirrors the CIDR. The only catch is that unless the Aadhar Act is amended, the police cannot legally store other biometric parameters such as IRIS scans and vein prints. This is why successive NCRB conferences have recommended amending the Aadhaar Act.

UIDAI’s denial might look like a principled opposition, but it is also a reflexive mechanism to ensure that NCRB or other agencies don’t catch onto the fact that there are serious quality issues that plague the Aadhaar biometric database. For instance, biometric mixups affect (officially) nearly 2 crore Aadhaar holders and while the image formats are compatible, the minimum quality of capture for Aadhaar is a mere 52%.

Parallel biometric datbases

While Section 29 of the Aadhaar Act only deals with sharing of biometrics, it does allow limited access to the demographic data by allowing police to become KUA/AUAs and through other means.

The limited access to demographic data also allows the state police to build their own parallel fingerprint databases – something that is currently happening in at least three states. What’s worse is that entries are typically not deleted, as mandated by the Identification of Prisoner act, if an arrestee is acquitted later.

This allows convergence of the crime and civilian databases, as indicated by the-then deputy director general of the UIDAI, Ashok Dalwai, way back in 2013, leading to the implication that this had always been the original design.

A vast database that allows other entities (including states) to build their own parallel (and bigger) databases with parallel biometrics, by design, is exactly the architecture that an all encompassing surveillance state would need. Such an architecture makes the legal construct of “consent and purpose limitation”, as enunciated by the nine-judge privacy bench, impractical and unimplementable by design.

This is why the Srikrishna committee, while recommending amendments to the Act, has kept Aadhaar out of the purview of the proposed data protection bill.

The typical response of the Supreme Court is to issue guidelines that needs to be followed by the state (PUCL vs Union of India, 1996), when it encounters complex questions, such as balancing the right to privacy and the requirements of law enforcement agencies.

But what if such an approach would meet nothing but failure, because the architecture of the project is designed to make guidelines based on “consent and purpose limitation” irrelevant?

While the software revolution sweeps by and eats the world, will it also end up eating the law and weaken constitutional rights? With the Supreme Court set to rule on the Aadhaar case, we will know soon enough.

(With inputs from Anuj Srivas)