Imre Bangha of Oxford University, in a piece published on The Wire on September 12, 2020, referred to my 2019 essay – ‘Hindi was devised by a Scottish linguist of the East India Company – it can never be India’s National Language’ – in the very first paragraph.

Bangha introduced my essay by saying ‘those who resent the political role of Hindi in 20th century nationalism’: a comment that is unfortunately misplaced. My essay was a reaction to the Hindi imposition drive in the 21st century by the current Hindutva regime that wants to enforce Hindi as our ‘National Language’. This ‘social engineering mission’ is not acceptable to the non-Hindi speaking regions of India.

My essay argues on the line that India does not need a singular national language and provides the reasons for it. I was not resenting any political role of Hindi in 20th century nationalism. Bangha must already know that Vande Mataram – the rallying cry of 20th century Indian nationalism and the freedom movement – appeared in a novel written in Bengali, not Hindi.

Bangha’s explicit pro-Hindi sentimentalism – that makes him misunderstand, or even overlook, evidential facts – is revealed further when he bypasses the all-critical role of John Gilchrist and Fort William College in Calcutta, by focusing much of his piece upon comments made by George A. Grierson, and his ‘unclear’ ideas about Hindi being ‘a language, a speech and then a dialect.’

Bangha goes to discuss Rekhta and the Nagari script that no one has claimed to have been devised by the British, who only played a pivotal role in popularising it.

Also read: Pushing Hindi as Politics, Not Hindi as Language

Bangha concludes his piece by saying, ‘Although the colonial claim that the British created a new language – a language appropriate to the modern needs – has taken deep roots in contemporary thinking, it is only partially justified…the British created a highly Sanskritsied style of Khari boli perceiving it to be a Hindu speech variety.’

The last line only supports what was pointed out in my essay: the colonial British bifurcated secular Hindustani into two separate modern languages for Hindus and Muslims.

Gilchrist also claimed the same – as quoted in my essay – ‘bifurcation of Khariboli into two forms – the Hindustani language with Khariboli as the root – resulted in two languages (Hindi and Urdu), each with its own character and script.’

“In other words” – what I wrote in my essay – “what was Hindustani language was segregated into Hindi and Urdu (written in Devanagari and Persian scripts), codified and formalised.”

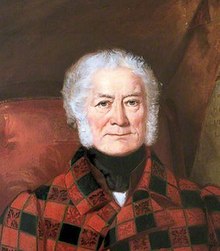

Blanconi; Dr John Borthwick Gilchrist (1759-1841); UCL Art Museum; Photo: Public domain

And this was achieved through the initiative of the Scottish linguist and the employee of East India Company, John Gilchrist (1759-1841) and the Fort William College in Calcutta (1800-1854).

This pivotal piece of history in modern Hindi’s origin is glossed over by Bangha who says, “Hindustani was standardised into its single modern grammar by Urdu intellectuals in the 18th century and by print culture and Hindi intellectuals in the 19th century. Although Fort William College also had its share in it, claiming its entire agency is exaggeration.”

By saying the above, Bangha completely omits the fact that the very first printed book in modern Hindi – Devanagari or Nagari type-set – was not written by someone with a surname of Sharma or Tripathi, but was written by John Gilchrist.

And it was a work titled ‘A Grammar of the Hindoostanee Language, or Part Third of Volume First, of a System of Hindoostanee Philology’, Calcutta: Chronicle Press, 1796.

The first two volumes of the grammar were included in the very first work that Gilchrist published: ‘A Dictionary: English and Hindoostanee’, Calcutta: Stuart and Cooper, 1787-90.

The grammar of modern Hindi – as we know it to be now – was ultimately standardised by John Gilchrist of Fort William College.

In order to popularise Hindi, Gilchrist recruited and paid native writers to produce works in accordance to that grammar.

It was also Fort William College that got these works – vernacular textbooks, dictionaries and literary creations – published by the ‘Serampore Mission Press’ – one of the earliest printing presses in India, and got them widely disseminated all across India.

These inconvertible facts make it unreasonable to say – like Bangha has said in his piece – that the ‘entire agency’ of the college’s role is an ‘exaggeration’.

One also needs to point out that the Devanagari or Nagari type-face or font was developed by the Orientalist, typographer and founding member of The Asiatic Society, Charles Wilkins and one of the employees of Wilkin’s printing press in Calcutta, Panchanan Karmakar: a Bengali born in Hooghly district. The reference to this is print expert Arun Bapurao Naik, son of legendary Bapurao Naik, the author of Indian Bookprinting and other notable works.

§

Fort William College in Calcutta – under Gilchrist’s leadership – became a centre for both Hindi and Urdu prose. It started within the premises of Fort William, in the location, where the Raj Bhavan – or the present Governor’s residence – was built (between 1799 to 1803) by Governor-General Wellesley.

So the college was moved in 1800 to another building – originally designed by Thomas Lyon in 1777 – in the nearby area, now known as the Dalhousie Square or the B.B.D Bag.

Several structural changes were made to the building to accommodate a new hostel, several halls (for examination and lectures) and four libraries dedicated to the cause of Hindi, Urdu and other languages.

The institution gathered writers from all over India to compose Hindi, Urdu and other vernacular texts; and hence, even after it moved out of the B.B.D Bag building in 1830, the 150-meter long premises of the former college still continues to be known as the “Writers’ building”: a famous landmark of Calcutta; the old secretariat building of the State of West Bengal and the actual historical birthplace of modern Hindi.

Devdan Chaudhuri is the author of the novel Anatomy of Life. He is also a poet whose works have featured in Modern English Poetry by Younger Indians published by Sahitya Akademi; a short story writer; an essayist on politics and culture and one of the contributing editors of The Punch Magazine. He lives in Kolkata.