Something very strange – and more than a little scary – happened at around 10pm on Sunday, October 27. Out of the blue, viewers of BBC2 found themselves watching the latest film by British director Jonathan Glazer, perhaps best-known for the unsettling Scottish-set science fiction horror Under the Skin.

The five-minute film, The Fall (available on BBC iPlayer), follows a masked gang as they capture and then attempt to execute a lone man. In one particularly disturbing scene, the mob pose with their victim in a blurry snapshot, as if with an animal they have killed on a hunting expedition.

But was the film just a Halloween horror? Or does it have profound things to say about the current state of the world?

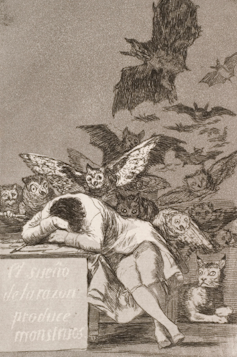

The film actually owes much to ‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters‘, an etching by Spanish Romantic artist Francisco José Goya y Lucientes. Goya’s work is the image of a nightmare. Eerie owls, bats, cats and ghouls descend upon a sleeping artist, omens that represent foolishness, ignorance and the persistence of superstition. It is grotesque and demonic, containing imagery found throughout ‘The Caprices’, the 80-piece collection of the artist’s work published in 1799.

‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters’ has inspired and been reworked by several contemporary artists – and most recently by Glazer.

Francisco Goya’s ‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters’. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The BBC’s accompanying press release for The Fall is quick to point out the inspiration drawn from Goya’s work. The creators expect that viewers will “project their [own] preoccupations and interpretations” onto this purposefully vague and evocative short film. The Fall is an artistic vignette about the current political moment, an intervention intended to spark discussion and highlight the audience’s fears – and, perhaps, hopes – for the future.

The death of reason?

Like The Fall, Goya’s ‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters’ is openly ambiguous in its sketched, dark and nightmarish style – and visualises the sense of foreboding that comes during moments of great uncertainty.

Goya’s work often questioned the role of the individual during periods of change that seem beyond their control. And while Goya critiqued the Roman Catholic clergy and those who facilitated their actions (either through support or inaction) during the horrors of the Inquisition, later artists have seen his works’ contemporary relevance and how they highlight the individual’s tendency to ignore or metaphorically sleep through crises.

A further foray into the contemporary Gothic aesthetic that Glazer established in ‘Under the Skin’ and ‘Birth’, The Fall draws on Goya – and shifts between crisp digital images and fuzzy footage.

At times, it is as if the footage has been filmed on a phone, replicating the viral images we now see so often posted online and rapidly shared without any knowledge of their origin. And, like Goya, Glazer uses this ethereal dystopian imagery to critique contemporary politics and the “us versus them” mob mentality that haunts issues such as Brexit, Trump’s rise to power and the migrant crisis.

In the film, the group of masked men and women shake the lone victim from a tree – perhaps a reference to the lone activist or marginalised person speaking out against the status quo (a literal tree-hugger). Meanwhile, other members of the anonymous mob lurk in the darkness and watch the victimisation in real time. Like their online equivalents, their masks allow them to act with the intoxicating power of anonymity.

Also read: Cli-Fi: Why Imagining Both Utopian and Dystopian Climate Futures Is Crucial

The victim is then hanged, dropping into a hole for a tense 86 seconds to what we assume will be his death. The scene strongly echoes the hanging trees associated with the Jim Crow-era US or the gallows that once provided public entertainment in the UK. As Glazer told the Guardian:

A mob encourages an abdication of personal responsibility. The rise of National Socialism in Germany for instance was like a fever that took hold of people. We can see that happening again.

The imagery is particularly poignant in the light of US president Donald Trump repeatedly using terms such as “lynching” and “witch hunt”, language he appropriates to rile up his base and the opposition.

Dropping into political satire

Brexit still looms large for the British public. The promise of a Halloween exit was just another knot in the unravelling rope of the UK’s seemingly endless fall out of the EU.

The lack of a clear end point for this current situation produces feelings of discomfort, anxiety and unease. It is also this feeling that Glazer purposely attempts to replicate, noting that “fear is ever-present”. The fear of the unknown and the divisive nature of the decision to leave the EU has created a state riven by political and cultural tribalism.

Also read: What South Asian Sci-Fi Can Tell Us About Our World

In the week for guising and in the run-up to mischief night and the autumn fire festivals, The Fall aptly recalls the masks and morbidness of the season while commenting on our present dystopian moment.

But at its end, The Fall offers a moment of hope. The lynching victim has reached out to the sides of the hole he has been dropped down and stopped his lethal fall. And as the film draws to a close, he begins climbing slowly back up towards the light.

Maybe, just maybe, we can also stop, or at least slow down, the present political free fall. But we do need to start by reaching out.

Amy Chambers, Senior Lecturer in Film Studies, Manchester Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.