Like the New York Times v. Sullivan case fifty years ago, The Wire defamation case too is about the ‘breathing space’ of free speech, criticism and truth.

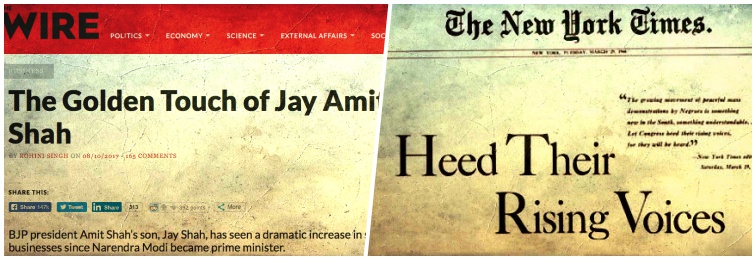

Left: The Wire’s article ‘The Golden Touch of Jay Amit Shah’. The New York Times’ advertisement ‘Heed Their Rising Voices’. Credit: The Wire/Wikipedia

Sixteen years before the word ‘Justice’ was prefixed to her name, Elena Kagan (then an assistant law professor at the University of Chicago) wrote an insightful book review evaluating Anthony Lewis’s book Make no law: The Sullivan case and the First Amendment. Kagan begins her review stating “New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) is one of those rare cases – perhaps especially rare in the field of First Amendment law – in which the heroes are heroes, the villains are villains, and everyone can be characterised as one or the other”. It is worth revisiting Lewis’s story of the Sullivan case in light of the defamation case filed by Jay Amitbhai Shah against The Wire and its employees for Rohini Singh’s article ‘The Golden touch of Jay Amit Shah‘.

Defamation in the 21st century AG (After Goswami) and the form of journalism he inspires has also become less black and white as an issue of media censorship, with the media often trampling upon people’s reputations without any fear. And then there are cases such as the one against The Wire in which, as Kagan would say, heroes are heroes and villains are villains. If it is the balance sheet of Jay Shah’s company which is the cause of aggrievement in the present case, in Sullivan, it was a poster that prompted a historic defamation claim against the New York Times – but in both instances, the real issue is much larger than the tarnishing of individual reputations or even the chilling effects of defamation.

‘Heed Their Rising Voices’. Credit: Wikipedia

The Sullivan case arose in the context of the civil rights movement in the United States with a sharp political divide emerging between the liberal states and the conservative southern states. On March 29, 1960, the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South jointly posted an advertisement – ‘Heed Their Rising Voices’ – in the New York Times. The ad exposed efforts by southern states and the police to subvert the civil rights movement, calling them “southern violators of the constitution”.

In particular, the poster described police atrocities in Montgomery, Alabama, but it also included a few relatively insignificant factual errors such as the number of times King had been arrested. This prompted L.B. Sullivan, the police commissioner of the City of Montgomery, Alabama to initiate a libel suit against the New York Times.

In his history of the case, Anthony Lewis reveals that the Sullivan case was only the first of a series of cases that were filed against the press by influential public personalities from the south which had one clear aim – muzzling the media’s coverage of the civil liberties movement and the strategy in each case was the same – libel suits against the newspapers, demanding heavy punitive damages ($500,000 in each of five cases). The New York Times, during this period, was beset by its own internal and monetary problems and there was a real danger that the paper would not have survived this onslaught. There was also the very real danger that had the legal action succeeded it would have entirely silenced smaller media players. In its decision affirming the free speech rights of New York Times and the press in general, the Supreme Court significantly redefined the legal and political stakes involved.

Firstly, they called the bluff of the lawsuit, acknowledging that underlying the defamation claim was a far more pernicious conspiracy – to silence political criticism and what the case stood for was not merely whether a newspaper would survive such law suits but whether free speech and public criticism could survive “the pall of fear and timidity imposed” upon it.

Secondly, they brushed aside the minor factual errors in the advertisement and inaugurated a new doctrinal test – which required that public officials had to prove “actual malice”, i.e., that statements were made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of whether it was true or false.

The Sullivan judgment has been celebrated globally as one of the most significant decisions on freedom of press, and also one that has been regularly cited by the Indian Supreme Court in its free speech decisions. This brings us back to the present case and its moral and legal repugnancy. That defamation cases have been the handmaiden of political and corporate censorship in India is well documented, and Rajeev Dhavan in his book Publish and be Damned: Censorship and Intolerance in India argues that imperfect as the jurisprudence of free speech in India is, it at least provides one with a platform to challenge unreasonable acts of the state. The real challenge for Dhavan is how to tackle lumpen threats that also expertly use the law in strategic ways.

Penelope Canan and George W. Pring coined the phrase SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) suits to describe the use of lawsuits by deep-pocketed corporates/individuals to silence critics/whistle-blowers by cornering them via long drawn and expensive litigation. The primary objective of the SLAPP suit is not to secure adjudicatory relief but to threaten, intimidate or coerce the other party into silence or, in the alternative, burden them with the costs of mounting a defence in a system which has a reputation of favouring big players over smaller ones.

In addition to the well known strategy of SLAPP suits, Dhavan invents a new acronym KICKS (Kriminal Intimidatory Coercive Knock Out Strategies) to describe a mode of using the law for the most illegal purposes by the most lawless groups. Recall the way M.F. Hussain was ‘kicked’ out of the country by the many criminal cases filed against him.

What is unique about defamation cases is the fact that defamation is both a civil and criminal offence, allowing claimants to combine the monetary punishment of SLAPP suits with intimidation by the criminal justice system. It is also important to note that while the intention of the defaming party is relevant for any action brought under Section 499 of the IPC, it is irrelevant for the purpose of any civil case. Furthermore, a criminal action and civil action for defamation are not mutually exclusive, and both can be pursued simultaneously. In the present case filed against The Wire, it is difficult to distinguish whether this is a private complaint filed by the owner of a company or an action initiated by the state since the Additional Solicitor General Tushar Mehta has been given permission (by his own apparent admission, two days before the story was even carried) by the law ministry to represent Jay Shah. While there is indeed something rotten in the state of Denmark, the “foul and pestilent congregation of vapours” clearly flows much further.

The primary reason for choosing a criminal remedy over a civil one is the efficacy of the system and the process as punishment itself. Initiating a criminal complaint means that the accused are obliged to appear before the court till the case is over, often necessitating travel to distant areas where the case has been filed. While there are a number of defences available against a charge of criminal defamation, that is rarely the point, since it is the procedure itself that is the punishment. Added to this is the fact that a defamation case can be filed at any place where the publication was available, which in the case of the internet can mean that a case can be filed just about anywhere. There is, by now, a pretty long history of the use of defamation laws by corporations to silence any form of critique or action by activists. This has even been acknowledged by the Supreme Court and in Indian Oil Corporation v. NEPC, the court observed that there was “a growing tendency in business circles to convert purely civil disputes into criminal cases”.

What is unique about defamation cases is the fact that defamation is both a civil and criminal offence, allowing claimants to combine the monetary punishment of SLAPP suits with intimidation by the criminal justice system. Credit: Ahdieh Ashrafi/Flickr CC 2.0

On the other hand, civil proceedings have their own advantages and the high court fees (fixed on the basis of quantum of damages sought) effectively ensures that only those with the deepest pockets can afford to claim large damages. Defamation cases have therefore become the litigation sport of the privileged and it is often the case that powerful individuals and corporations do not file defamation cases to win or to safeguard their reputations, rather their interest lies in obtaining immediate injunctive relief and drowning their opposition in protracted and expensive litigation.

The Indian legal system has been relatively conducive to SLAPPs. While traditionally, the SLAPP suit found its victim in activists/whistle-blowers, the target base of this instrument has expanded to cover academicians expressing objective opinions or making fair observations. In recent times, corporations have targeted academic commentators and Spicy IP, a popular Indian blog discussing intellectual property law has been the subject of defamation cases by top corporates such as NATCO and Bennett Coleman. Another commons strategy used in SLAPP suits is ‘forum shopping’ in which parties choose litigation venues which are either advantageous to them or impose a high transaction cost on the defendant. Forum shopping, which has been also described as “libel tourism”, is best illustrated by the Caravan defamation suit in which a case was filed in Silchar even though all the primary actors were based in Delhi.

Slapping back

The Delhi high court, in M/s Crop Federation v. Rajasthan Patrika, demonstrated how despite the absence of an anti-SLAPP legislation, Order 7 Rule 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure can be used to dismiss SLAPPs. In this case, the plaintiff was a company whose members and shareholders were insecticide manufacturers, licensed to produce such goods. The first defendant was the newspaper Rajasthan Patrika and the remaining defendants were employees with the newspaper. The plaintiff approached the high court and claimed to be aggrieved by several articles published in Rajasthan Patrika by the defendants, with respect to the alleged levels of pesticides the company used and the alleged harmful effects these have on plant and animal life. The plaintiff argued that these articles tended to defame all pesticide and insecticide manufacturers, which essentially included all the plaintiff’s members and shareholders.

The court had said:

“The present suit contains all the ingredients of a SLAPP suit. A strategic lawsuit against public participation (SLAPP) is a lawsuit intended to censor, intimidate and silence critics by burdening them with the cost of a legal defense until they abandon their criticism or opposition. Winning the lawsuit is not necessarily the intent of the person filing the SLAPP. In such instances, the plaintiff’s goals are accomplished if the defendant succumbs to fear, intimidation, mounting legal costs or simple exhaustion and abandons the criticism. A SLAPP may also intimidate others from participating in the debate”.

Justice Ravindra Bhatt, who delivered the judgment, went on to make further observations about the dangerous tendency of SLAPP suits in the Greenpeace case, where he applied the Bonnard principles to defamation cases and refused to grant an injunction on the grounds that it would be unreasonable to fetter the freedom of speech before the full trial takes place, where each of the parties can argue in detail with the help of additional evidence.

It is also important to note that sometimes a defamation case can itself be the occasion for the mobilising of public opinion against the person or company filing the case. One of the longest litigations (running to two decades) in the UK was the infamous McLibel case in which McDonalds sued two activists for pamphlets they had issued targeting McDonalds. McDonalds eventually spent up to £10 million in legal costs while the activists raised £40,000 from the public to mount their legal defence. The court finally delivered its 762-page judgment in 1997. Justice Bell held in favour of McDonalds on some of the extreme claims that had been made by the activists including the allegation that McDonalds was to blame for starvation in the Third World or had used lethal poisons to destroy vast areas of Central American rainforest.

However, he also held – in what was seen as a public relations disaster for the corporation – that McDonalds had “pretended to a positive nutritional benefit which their food did not match”, had exploited children in its advertising, and paid low wages, “helping to depress wages in the catering trade”. McDonalds did not claim the damages awarded to it. Instead, it was relieved the case came to an end, given the media’s portrayal as a case of David versus Goliath.

While the case has many lessons about how a SLAPP suit itself can be converted into a critical media event that can generate further adversity for companies, the strangle hold that companies often have over the media makes it more difficult for this strategy to work in the contemporary. The phenomenon of paid news, for instance, more or less ensures that companies who are using defamation cases to silence critics are unlikely to face challenges from other media houses. In conclusion, if we recognise that corporate and political censorship takes a form similar to either state or lumpen bullying, there is a need to develop principles that proactively protect citizens against corporate bullying.

The Supreme Court in Rangarajan held, “Freedom of expression cannot be suppressed on account of threat of demonstration and processions or threats of violence. That would tantamount to negation of the rule of law and a surrender to black mail and intimidation. It is the duty of the state to protect the freedom of expression since it is a liberty guaranteed against the state”.

The need of the hour is a judicial recognition that bullies do not necessarily wield lathis and can often come dressed in impeccable suits.

Let us not be mistaken into thinking that this case is only about The Wire or the defaming of individual reputations. Like the Sullivan case 50 years ago, this case too is about the ‘breathing space’ of free speech, criticism and truth – and just as with air, democratic breathing spaces, when polluted, do not affect individuals alone but threaten to choke anyone else who dares to speak up.

Lawrence Liang is a professor at School of Law, Governance and Citizenship, Ambedkar University Delhi.

Comments are closed.