Even as nations all over the globe are yet to recover from a pandemic’s catastrophic impact, most South Asian countries – in recent months – have been badly hit by multiple crises. From Afghanistan to Myanmar to Pakistan, and now, Sri Lanka, each nation’s political economy landscape appears to be in a depressing situation.

Sri Lanka’s economy, in recent months, started experiencing, what economists refer to as a ‘twin crisis’: in form of a combined balance of payment and sovereign debt crisis.

This happens usually when a nation’s growth outlook remains weak, its foreign currency reserves (mostly in US$) are drying up (or have already dried up), and, the government finds it difficult to honour its (external) debt obligations. Solvency issues may affect governments at first but ultimately the crisis effects pass on to the people in the worst possible ways.

In the past, countries like Argentina, Mexico and Brazil have been often affected by such ‘twin shocks’, taking decades to recover.

What happened in Sri Lanka?

The IMF in a recent report explained how COVID-19 severely hit the Sri Lankan economy. The annual GDP growth rate of 2.3% in 2019 became -3.6% in 2020.

During the pandemic, the Lankan government promptly announced a series of relief measures through a macroeconomic policy stimulus; an increase in social safety net spending, and loan repayment moratoria for affected businesses.

These measures were simultaneously complemented by a strong vaccination drive which helped in restoring the GDP growth to a recovered rate of 3.6% in 2021, with mobility indicators largely going back to their pre-pandemic levels and tourist arrivals starting to recover in late 2021.

Nevertheless, the pandemic, necessitating several strict lockdowns, caused a colossal loss of tourism receipts: one of the main revenue-generating sectors for the nation. Adding to this, the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government’s own pre-pandemic policies had serious flaws.

Figure: Sri Lanka Tourism Revenue Receipts (in US$ million)

The Rajapaksa government introduced populist tax cuts prior to the pandemic, limiting the government’s revenue options from corporate tax revenue. Foreign remittances from Sri Lankan workers abroad were drying up already. The adverse impact of COVID-19 and the announced relief spending measures led to higher government spending (with a weak revenue base) made fiscal deficits to be larger than 10% of GDP in 2020 and 2021, while the economy witnessed a rapid increase in public debt to 119% of GDP in 2021.

Figure: Sri Lanka Government Spending vs. Government Revenue

Figure: Sri Lanka Foreign Currency Reserves (in US$ million)

Sri Lanka lost access to international capital markets in 2020, prompting a decline of international reserves to critically low levels and large-scale direct lending to the government by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL). External debt repayments and a widening current account deficit led to foreign exchange (FX) shortages, while the official exchange rate remained de facto fixed since April 2021.

Figure: Sri Lanka Total Gross External Debt vs. Foreign Currency Reserves (in USD Million)

Making matters worse was Rajapaksa’s pivot last year to organic farming with a ban on chemical fertilizers that triggered farmer protests saw a decline in the production of critical tea and rice crops.

Inflation rates continued to climb up, reaching double digits in December 2021, while reflecting the cascading effects of imported inflation from rising oil-food import prices, supply shocks, and a pickup in domestic consumer demand, amidst a loose monetary policy.

Figure: Sri Lanka inflation rate (%) and consumer spending

Bad macroeconomic policy management further accentuated the economic crisis making the common citizenry suffer.

Sri Lankan people in recent weeks have taken to the streets to protest against the Rajapaksa government due to rising power cuts, their difficulty to get food at affordable prices, while queuing outside gasoline pumps that are now being guarded by the army.

The political turmoil, surfacing from the economic crisis, has made it difficult to gauge how the situation will unfold for the Rajapaksa government in the days ahead.

This week, Rajapaksa’s ruling party, Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) lost its majority in parliament as 42 MPs (14 from Sri Lanka Freedom Party, 10 belong to constituent parties of the government, and 12 are SLPP MPs, among others) announced they would sit independently. Rajapaksa said that will not resign, but was ready to hand over the government to whichever party holds 113 seats in parliament.

Whichever government comes/stays in power, would need to adopt a long term approach to fix a struggling economy.

What the Lankan economy would need is a robust path towards revenue based fiscal consolidation. Reforms must focus on strengthening VAT, income and corporate taxes, through gradual rate increases and base broadening measures. Fiscal adjustment would need to be accompanied by energy pricing reforms to reduce fiscal risks from loss-making public enterprises.

Near-term monetary policy tightening is needed to ensure that the recent breach of the inflation target band is only temporary. Institution building reforms, such as revamping the fiscal rule, would also help ensure the credibility of the strategy, as the IMF report suggests.

Other (longer-term) reforms would need to include the creation of a flexible exchange rate policy and a medium-to-long-term debt reduction strategy, while ensuring most government spending in targeted social areas continues for developmental objectives (in areas of healthcare, education and social security goals).

Sri Lankan army commandos walk past the damaged vehicles set on fire by demonstrators near President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s residence during a protest in Colombo, Sri Lanka April 1, 2022. Photo: Reuters/Dinuka Liyanawatte

Lessons for India

While the Sri Lankan economic crisis may not directly impact India for now, the crisis itself offers useful political economy lessons for the Indian government.

A majoritarian government (run by leaders like Rajapaksa or Narendra Modi) announcing populist measures amidst a low-growth performance cycle creates macroeconomic crisis scenarios over time.

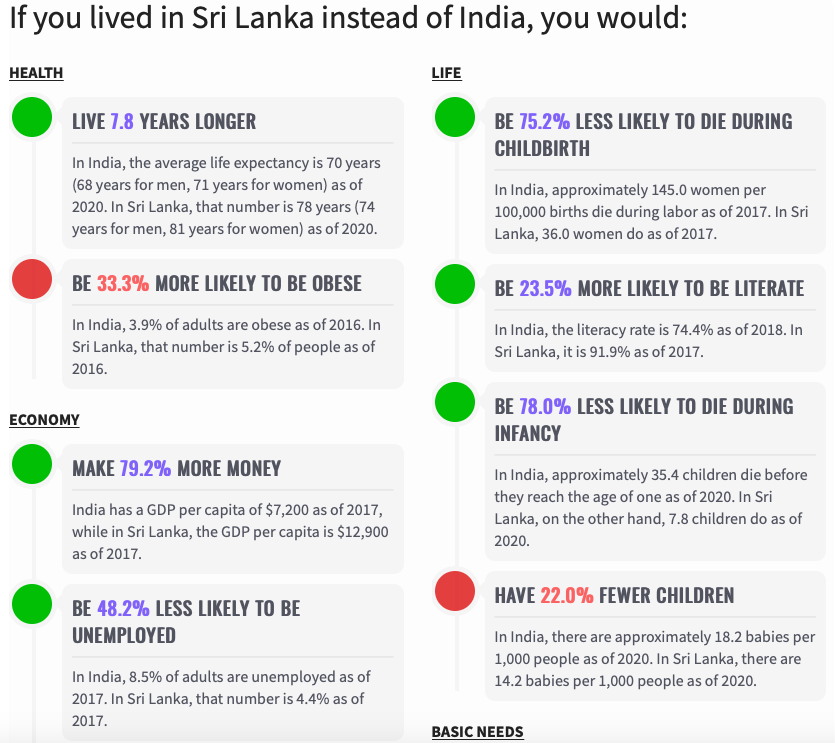

Unlike Sri Lanka, India’s per capita income and performance in social sectors like healthcare, education and social security is worse (see figure below).

On inflation and high youth unemployment, Sri Lanka’s inability to address the growing price rise and a crisis of job creation amongst its youth-led to street protests and angst against the incumbent government. India’s unemployment and joblessness crisis is far worse – in aggregate. Inflation too has remained high with the RBI struggling to keep consumer prices low.

The idea here is not to compare Sri Lanka with India as like-with-like. They are two different and geographically distinct nation-states with different social, political and economic features.

Still, irrespective of the difference in country sizes, the nature of social policy direction for Sri Lanka – before the crisis – remained closely aligned to improving ‘quality of life’ for its people, especially in the context of ensuring access to affordable healthcare for the masses.

India, on an aggregate, and in relative comparison to policy direction, performed miserably in this regard (see India’s performance on healthcare and nutritional outcomes in comparison to Sri Lanka prior to 2016). A comparison table below compiled based on the World Economic Forums’ Global Competitive Report 2015/16 and World Bank Group’s Doing Business Report 2016 provides a brief overview of these two countries.

A lot changed for Sri Lanka – and its political economy after 2016.

Rajapaksa’s politics, style of governance, and gross disregard for democratic procedures (as evident from the constitutional amendment passed in 2020), bear close resemblance to the way Modi has led India. Centralised ad hoc policy measures, cutting taxes for populist reasons (prior to the pandemic), inability to collect estimated revenue for government’s spending needs, seeing a rise in government debt, offering limited autonomy to central bank for targeting inflation, while banning chemical fertilisers – to aggressively thrust organic farming on Sri Lankan farmers, all, strike a worrying resemblance to a troubling state of affairs being observed in India’s own (macro) politico-economic scenario.