An alarming new report from the V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) Institute at the University of Gothenberg in Sweden states that by the end of 2022, 72% of the world’s population (5.7 billion people) lived in autocracies, out of which 28% (2.2 billion people) lived in “closed autocracies”.

The report titled Defiance in the Face of Autocratization has further asserted that “advances in global levels of democracy made over the last 35 years have been wiped out.”

The findings of this report should be a cause of global concern for politicians and policy-makers alike.

The report indicates that today there are more closed autocracies than liberal democracies and only 13% of the world’s humans (approximately one billion people) live in liberal democracies.

Amongst the various population-weighted indicators that the report uses to make its determinations on the health of democracy in various countries, it pays particular attention to freedom of expression (declining in 35 countries), increased government censorship of the media (declining in 47 countries), the worsening state repression of civil society actors (going downhill in 37 countries) and a decline in the quality of elections in 30 countries. It also lists Armenia, Greece and Mauritius as “democracies in steep decline”.

Undoubtedly, the last decade has seen the increasing power of autocratic political regimes across the world. Further, when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in 2020, many countries scrambled to centralise power and suspend parliamentary decision-making in an attempt to manage the pandemic. Such countries used the pandemic to pass legislations that impinged on their citizens’ rights and freedoms.

Some countries also used the pandemic as an excuse to allow the executive in those countries to assume disproportionate power, vis-à-vis citizens. For instance, in Hungary President Viktor Orbán assumed the power to rule by decree in 2020, then declared a “state of medical crisis” when he was criticised, which allowed his government to keep issuing decrees. In 2022 he declared another state of emergency pursuant to the war in Ukraine.

In the United States, the state of Kentucky outlawed fossil fuel protests and a federal appeals court in Texas upheld a ban on abortions which was to foreshadow the overturning of the Roe v Wade judgment in 2022. In Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu suspended the Knesset and postponed his own trial by suspending the courts and increasing surveillance.

In India, the government wasted no time in announcing a new domicile law for Jammu and Kashmir in April 2020 that allowed people who have resided there for 15 years or those who have studied there for seven years and appeared in Class 10 and 12 exams, from acquiring permanent residence.

Clearly, the trend towards autocratisation in many parts of the world began intensifying in 2020. The V-Dem report lists 42 countries as “autocratising” at the end of 2022. This, it says, is a record number.

India is not an exception to this trend. A sudden lockdown in 2020 displayed how easily the lives of people at the margins of Indian society could be disrupted. In 2021, the V-Dem institute classified India as an “electoral autocracy”, while in the same year, Freedom House listed India as “partly free”. Also in 2021, the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance classified India as a backsliding democracy and a “major decliner” in its Global State of Democracy (GSoD) report.

Also read: India Has Significantly Less Academic Freedom Now Than 10 Years Ago: New V-Dem Report

The data made available by the GSoD report demonstrated that between 1975 and 1995 India’s representative government score moved from .59 to .69. In 2015 it was .72. However, in 2020 it stood at .61, i.e, closer to the score India had in 1975 when it was under Indira Gandhi’s Emergency. The GSoD report also listed India alongside Sri Lanka and Indonesia for the lowest score on the religious freedom indicator since 1975.

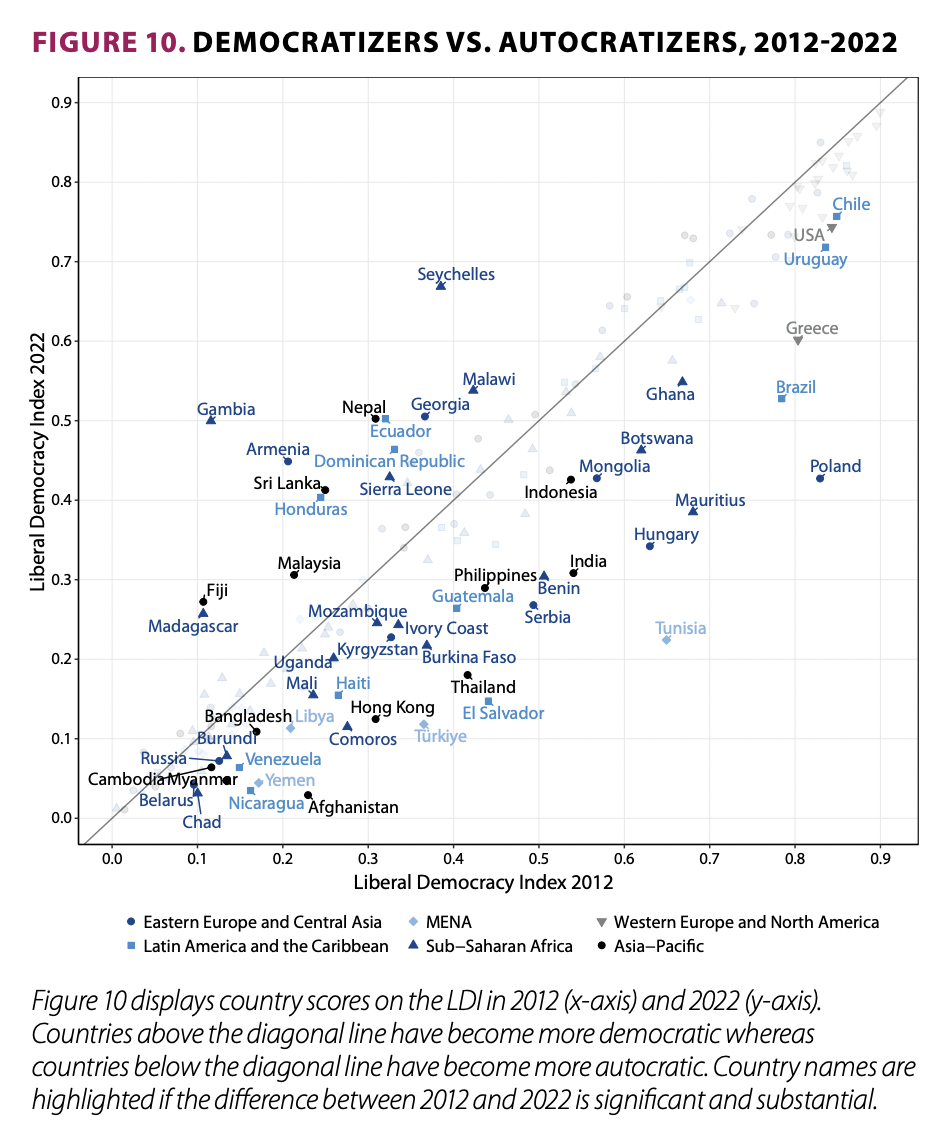

Therefore, it is unsurprising that the 2023 V-Dem report refers to India as “one of the worst autocratisers in the last 10 years” in a blurb on page 10 and places India in the bottom 40-50% on its Liberal Democracy Index at rank 97. India also ranks 108 on the Electoral Democracy Index and 123 on the Egalitarian Component Index.

Yet, the report concedes on page 24 that the process of autocratisation has “slowed down considerably or stalled” in some countries, including India, after they turned into autocracies.

The report also points out some characteristics of autocratising countries. These include increased media censorship and repression of civil society, a decrease in academic freedom, cultural freedom and freedom of discussion. The report states that media censorship and repression of civil society are “what rulers in autocratising countries engage in most frequently, and to the greatest degree”. It finds also that academic freedom and freedom of cultural expression have declined severely in Indonesia, Russia and Uruguay.

The V-Dem report also extends its analysis to indicators that bolster autocratisation. It says that disinformation, polarisation and autocratisation reinforce each other. It flags those countries that increased their democracy scores (The Dominican Republic, Gambia and the Seychelles) as countries that were able to check disinformation and polarisation. The report aptly targets disinformation as a tool to “steer citizens’ preferences” that is actively used by autocratising regimes to increase political polarisation. It classifies Afghanistan, India, Brazil and Myanmar as autocratising countries that have seen the “most dramatic” increases in political polarisation.

The report tries to end on an uplifting note by suggesting that all is not lost as some countries are moving towards more democracy – Bolivia, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Moldova, Dominican Republic, Gambia and Malawi.

To a lesser degree, it counts the Maldives, North Macedonia, South Korea and Slovenia as countries that are making a positive democratic U-turn. It is a little puzzling to see the Maldives listed here as reports from 2022 demonstrate that President Ibrahim Solih (the 2019 election of whom the V-Dem report sees as an indicator of democratisation) did outlaw the anti-India protests that had taken root in some parts of the archipelagic nation. Maldivian civil society actors questioned whether a president had the power to criminalise dissent.

Even so, the V-Dem report states that democracies can bounce back from autocratisation when a certain set of criteria are satisfied. These include mass mobilisation against an incumbent, a unified opposition working with civil society, the judiciary reversing an executive takeover, critical elections, and international democracy support.

Finally, the V-Dem report thinks that there is a shift in the global balance of economic power. It finds that inter-democracy world trade has declined to 47% in 2022 from 74% in 1998. 46% of the world’s Gross Domestic Product now comes from autocracies and democracies’ dependence on autocratic countries has doubled in the last three decades. It sees this dependence of democratic countries on autocratic countries for trade as an emergent security issue for democracies.

Vasundhara Sirnate is a journalist and political scientist and the creator of the India Violence Archive.