In Hindi cinema, the Dalit, as a person, remained distant from the normal imagination of a civilised person. Newton , and some films before it, have attempted to break this cycle.

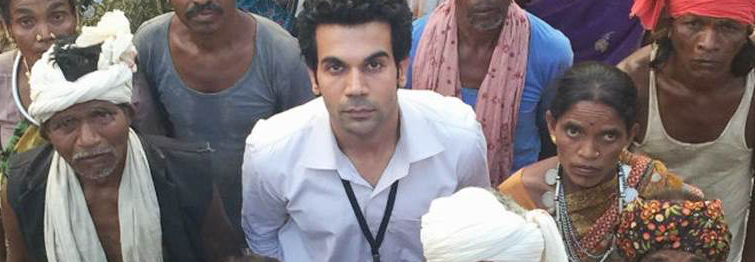

Newton has added a new element in on-screen Dalit characterisation. Credit: YouTube

There has been very little space for Dalit images in the century-long history of Hindi cinema. Our films have remained dominated by protagonists that unapologetically endorse upper caste cultural values and middle class privileges. The caste question is often invisible here and even when the Dalit characters emerge on the screen, they are often portrayed as archetypes.

However, a subtle evolution of Dalit portrayal in Bollywood is now emerging. Newton, directed by Amit Masurkar, offers a new look to the Dalit subject as it depicts the protagonist as a casteless free man, and thus ruptures the conventional norms and stereotypical representations.

In most reviews of the film, the social identity of the protagonist has been neglected and much emphasis has been given to its creative aspects. However, while Newton is without a doubt a very refreshing entry in the genre of commercial art house cinema, it offers a new social imaginary to depict its protagonist. By using certain symbolic social gestures and codes – in a very subtle way – a new Dalit ‘hero’ is offered to the audience. It appears that Bollywood is now ready to present a nuanced Dalit identity in its films, overcoming its earlier stereotypes.

The wretched Dalit

In the last three decades of political development, Dalits have utilised public institutions to gain an entry in mainstream spaces. Due to the state’s affirmative action policies, political development and modernisation, a section of Dalits have emerged as middle class, especially in urban centers. However, these changes have not been reflected in the popular narratives of Hindi cinema.

From early on in Hindi cinema, Dalit narratives have tended to revolve around atrocious social conditions and the struggles of Dalit protagonists (Achhut Kannya: 1936) and Achhut: 1940); later too, Hindi films kept endorsing stereotypical, precarious images of Dalits.

In the parallel – and progressive – cinema of the 1970s and 80s, the actualities of a Dalit life were shown with ethnographic precision, providing a slice of social reality to the audience. An archetype of the Dalits being wretched and surviving in brutal social conditions has dominated most of the filmic narratives. For example, in the Naseeruddin Shah-starrer Paar (1984), the Dalit protagonist is condemned to suffer even when he wishes to escape atrocious village life. In Satyajit Ray’s Sadgati (1981) the lead character Dukhi (Om Puri) dies because of stress, fatigue and hunger but does not challenge the authority of the Brahmin lord. In Aakrosh (1980) again, as a remedy to end the tragic conditions of his existence, the protagonist chooses self-destruction. These narratives showcased the anarchic and wretched social conditions in which Dalits have been trapped for centuries.

But the Dalit, as a person, remained distant from the normal imagination of a civilised person. The Dalit character is showcased as scantily dressed and primitive (Mrigaya, 1977), dark and pale (Damul, 1985) patriarchal and alcoholic (Ankur, 1974), corrupt and immoral (Peepli Live, 2010) and sometimes, even physically challenged (Lagaan, 2001). A Dalit character as a cheerful, happy and a normal family person has hardly been shown on screen.

Imagining a modern Dalit self

One of the first films that depicted a Dalit person with dignified characteristics was Prakash Jha’s Aarakshan (2011). This film tried to break certain stereotypes about the Dalit personality. Here, the protagonist (Saif Ali Khan) is a modern, educated and hardworking youth and not submissive to social humiliations. Instead, he is capable enough to respond with equal rigour and confidence. His social acceptability as a prospective groom for an upper caste Brahmin girl also breaks the conventional notion of endogamy and promotes him as an equal, autonomous individual.

However, the story lost all its social concern after the interval in order to promote Amitabh Bachchan as the main lead who fights for justice in his own ‘Gandhian’, philanthropic way. The Dalit character is reduced as a supplement to the main lead. In other films like Hu Tu Tu (1999), Aakrosh (2010) and Rajneeti (2010), the Dalit character has a substantive role, but a possibility that he can independently lead the battle against social ills and other criminalities is not explored beyond certain set boundaries.

Newton, by using creative techniques, introduces a righteous Dalit hero into Bollywood cinema. Credit: YouTube

Masaan (2015) was an interesting film that explored, in a very sensitive way, the burden of Dalit identity and the hope of the protagonist to escape the caste prison. Deepak (Vicky Kaushal) is a Dom by caste and going by the conventional logic of caste-based professions, his family burns dead bodies in Varanasi’s cremation ghat. However, Deepak, an engineering student, is a man with aspirations and desires and wishes to cross the borders of caste society. He falls in love with Shaalu, an upper caste girl. Importantly, when Deepak tells her about the work he does – of burning corpses – Shaalu remains firm and tells him that she will be with him even if her parents refuse. Such a narrative showcases a changed social psyche not only of the Dalit protagonist but also of the others. Similarly, in Guddu Rangeela (2015), the main lead Rangeela (Arshad Warsi) is a Dalit but dares to fall in love with a woman from a dominant caste and responds to caste violence with mainstream heroic logic.

These films tried to rupture the conventional stereotypes about Dalits as subservient powerless objects of oppression. They introduced a dignified, self-reflexive Dalit in the narrative that contested the social hegemony with heroic courage.

Is Newton a liberated Dalit hero?

Newton, in this respect, has added a new element in on-screen Dalit characterisation. One has to decode that the protagonist, Newton Kumar (brilliantly portrayed by Rajkummar Rao) belongs to the non-upper caste strata. The audience can see Babasaheb Ambedkar’s portrait in his living room for a second. In another scene, when Newton refuses to a marriage proposal, his father scolds him and reminds him that he will not get a Brahmin-Thakur girl for marriage.

Further, the reference ‘reserve’ for Newton is utilised in a symbolic way to showcase how governmental jobs are available with differentiated categories (reservation for the Scheduled Castes). There is no loud announcement of Dalit subjectivity here. However the above-mentioned symbolic gestures, done in an intelligent way, allow the audience to ponder about the social background of the protagonist.

Newton, by using such creative techniques, introduces a righteous Dalit hero into Bollywood cinema. He is an educated and honest youth who is committed strictly to his professional obligations as an Election Commission officer. He is starkly different from earlier depictions of Dalit characters as he is not at all burdened by or brutalised because of his Dalit identity. Instead, Newton is an independent rational thinking person, ready to fulfil his constitutional duty without any fear or prejudice. His fearless debate with the army commander, Atma Singh (Pankaj Tripathi), showcases his equal authority in the discourse of power. He must be aware of his lowly social past, but being an agent of the state, he empowers himself as a person with principles and challenges.

Newton represents himself as a duty-bound citizen and therefore his social identity does not restrict him from carrying out his constitutional obligations. Such a sense of freedom was not available to any Dalit character who has been portrayed in Hindi cinema before. Newton offers a new Dalit hero, who is born in the caste society but remains unaffected by its exploitative order and conflicts. His degraded caste identity is not a restriction in fulfilling his everyday social or professional duties. Like any other lead hero of mainstream Hindi films, he is free and his social identity is not directing his persona or social roles. Imagining Dalit characters with such unrestricted human aspirations is a new shift in Hindi film narratives.

On the critical front, Newton offers certain limitations too. One can surely ask to what extent such ‘caste free’ portrayal of a Dalit person will be welcomed in our socio-political discourses. Unlike the earlier mentioned films, which depicted caste atrocities and social discrimination as systemic caste-feudal oppression, Newton avoids any discussion on that part and focuses mainly on the protagonist’s duty as an agent of the state. The scriptwriter appears to be aware of the oppressive caste relationships that produce deep hatred and violence towards the socially deprived masses and therefore avoids any mention of the protagonist’s social identity. It appears that Newton’s veiled caste identity is helping him to perform his duty with righteous rigour. However, the inference that one draws is that if he were to reveal his social identity to the CRPF officer, his counterpart would probably not accord him with the same respect and concern. The nature of narrative would change if Newton were to announce his caste identity at any level. The narrative tries to suggest that caste should remain a meaningless category while functioning as an agent of the state.

Harish S. Wankhede is assistant professor at the Center for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, School of Social Sciences, New Delhi.

Comments are closed.