Ninety-seven percent of all incidents have occurred over the last three years since the BJP and Prime Minister Narendra Modi assumed power in May 2014.

Cow vigilantes stop a vehicle containing cattle at a road block near Chandigarh, India, July 6, 2017. Credit: Reuters/Cathal McNaughton

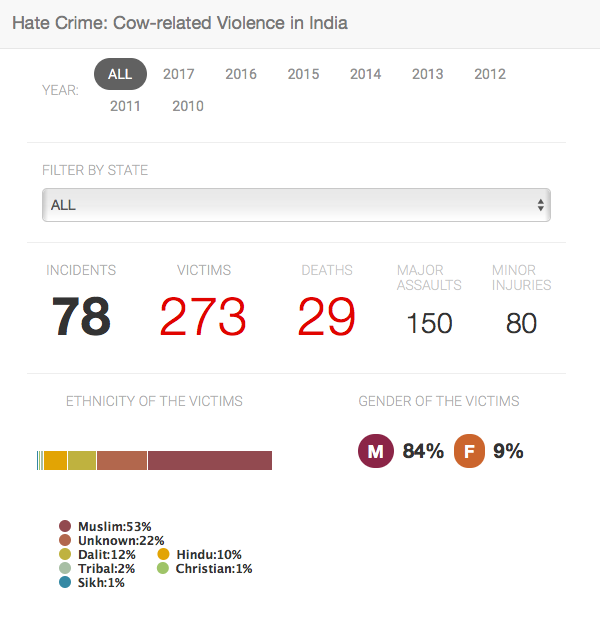

After the recent murder of a dairy trader by cow vigilantes on the Rajasthan-Haryana border, 11 deaths have been reported in 2017, the highest toll from cow-related hate crimes since 2010, from when IndiaSpend’s database records hate crimes. The database is being launched in a new, interactive format today.

No incidents of hate crime were reported in 2010 and 2011, but over the eight years since 2012, 29 persons have been killed in cow-related hate violence, 25 of whom were Muslim.

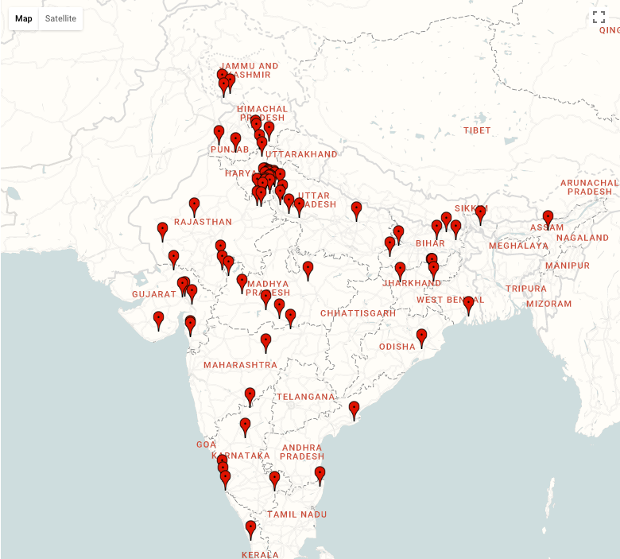

Until 2015, 76% or 13 of 17 cow-related hate crimes were reported from northern India. Since then, during 2016 and 2017 to-date, more incidents have been reported from the east, west and south of the country.

The NCRB does not collect data on cow-related hate crimes, the home ministry told the parliament on July 25, 2017. Our database does. Explore data over eight years here.

To build our database, our team collected, analysed and verified print and online news reports in the English media, which tend to have the widest nationwide coverage. All reported incidents were cross-referenced to eliminate discrepancies and, where needed, verified with local reporters or those who had filed original stories.

Our dataset includes the number of crimes committed each year since 2010, the severity of attacks and the reported cause of each incident. Most entries include the names of districts, towns and villages.

Since each observation is based on a newspaper report of the crime, details such as the severity of crime, the number of victims and their identities and ethnicities vary. While reportage in cases of death has been fairly comprehensive, in cases where victims are injured, the details provided differ depending on the extent of news coverage available.

Each crime is also geo-coded in the database. This is useful in viewing the geographic spread of such crimes and their concentration.

The database is an evolving initiative to record all hate crimes committed across India. Readers can report incidents too, which our team will then verify before adding them to the database.

Key findings

Our team gathered information about cow-related violence from 2010 onwards, and found no cases reported during 2010 and 2011. From 2012 until today, 78 cow-related hate crimes have been reported across the country. Most of these – 97% of all incidents – have occurred over the last three years since the Bharatiya Janata Party and Prime Minister Narendra Modi assumed power in May 2014. Only one incident each was reported in 2012 and 2013.

In the eight years since 2012, most of those killed – 25 of 29 persons – were Muslim. Of all victims – killed or injured, whose identity was reported in news reports – 53% were Muslim, 12% were Dalit, and 10% were Hindu. (Newspaper reports did not include the religious identity of 22% of the victims.) In a third of all cases – 26 of 78 cases – the police filed cases against the victims under cow-protection laws.

Geographically, from 2012 to-date, most cow-related hate crimes – 64%, or 50 of 78 incidents – were reported in north India. Since 2015, the attacks spread towards the east and south of the mainland at an increased pace.

Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, with ten incidents each, reported the most number of crimes, followed by Gujarat where seven incidents have been recorded.

Why this database

Hate crimes are violent manifestations of intolerance against entire communities. They have a deep impact on not only the immediate victim but also the community with which the victim identifies, affecting social cohesion and stability, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) said in its 2009 guide for framing hate crime laws.

For more insight into the Indian context, IndiaSpend spoke to experts in criminal law and human rights.

The effects of hate crimes are deeper and wide-ranging than those of other serious crimes such as murders and assault because their motives perpetuate hatred and instigate others to commit similar crimes, senior advocate Rebecca John, an expert on criminal law, told IndiaSpend. “In this case it would be minorities and those on the margins of a majority community.”

Attacks based on race, religion, caste or ethnicity in India often occur when the attackers believe that they have political cover and will not be prosecuted and punished, Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director for Human Rights Watch, an international non-governmental organisation, told IndiaSpend.

“When religious/political leaders go on stage or television and urge followers to take up arms to protect the cow, they are not merely inciting a single individual to commit a single act of violence. They communicate a sanction inciting several followers to commit such crimes across the country,” senior advocate Colin Gonsalves, founder of the Human Rights Law Network, told IndiaSpend. This not only motivates violence, it also destroys law and order because the police become reluctant to prevent the crime and/or arrest the perpetrators, he said.

As a society, we have not talked enough about cow-related violence or assessed its impact, John said, adding, “We hear the news… an incident in Rajasthan, another in UP, one in Delhi… but because of the prevailing atmosphere, the norm is to trivialise the incident and valorise the offender. Our conscience is not shocked as it should be.”

It is crucial for the state to respond immediately to establish the rule of law, and insist that any provocation or suspicion be handled by the criminal justice system and not through mob justice, Ganguly said. “Otherwise, people lose faith in the justice system, and there is risk of a cycle of revenge and violence,” she added.

Even in cases where those attacked may have been illegally smuggling cows for slaughter and tanning, the law does not allow a disproportionate response to the infraction. “The response to seeing a crime committed is to stop the perpetrator and wait for the police to deal with her or him – not to take matters into one’s own hands – especially if the so-called criminal is unarmed and pleads, with folded hands, for forgiveness and for his life. Unless there is a parallel threat of violence, and it is an act of self-defense, such a response is not acceptable under any law,” John said.

All the experts IndiaSpend spoke to said the political dispensation under which these crimes take place must be held accountable. “There appears to be some amount of political complicity in these attacks carried out in the name of cow protection,” said Ganguly, pointing out that in many cases – a third according to our database – instead of prosecuting the attackers, many of whom are allegedly linked to extremist Hindu groups affiliated with the ruling party, the police have filed complaints under laws banning cow slaughter against the assault victims, their relatives and associates.

“You cannot look at these stark statistics alone without understanding the political linkages,” John said. She added that the increase in the incidence of such crimes reflects a lack of will to uphold the law.

Ganguly agrees, and adds that the state cannot fail to prosecute criminal acts simply because the perpetrators might be supporters of the ruling party. “Once members of a political party are elected into office, they have to uphold the Constitution and rule of law,” she said, “Political patronage of criminals destroys institutions, causes a breakdown in human rights protections.”

Gonsalves too believes religious and political leaders who instigate such violence must be strictly prosecuted. “They are the masterminds behind these murders and assaults. In law we call this person ‘the main conspirator’ which is a term often used in dealing with terror cases. To my mind this sort of violence is no different than terrorism – in fact it is terrorism of the worst kind,” he said.

This is why a database is important, John said. “We are good at creating a record that suits us–the police, the courts and the government are complicit in this. To show this is not an aberration, and prove these are consistent patterns of violence on the rise that must be addressed, we need to create data. Else how are we to assess the need for parliamentary, judicial, or societal intervention to curb discrimination on ethnic identity?”

Our database is a starting point

Many countries explicitly penalise hate crimes through their criminal justice system. Some have separate criminal offenses for violent attacks carried out with racist or other hate motivation. Others provide explicitly for higher sentences for violent hate crime.

After the recent string of cow-related lynchings, some concerned citizens and law experts got together to draft a Manav Suraksha Kanoon (MASUKA Law) that would contain provisions to curb and punish mob lynching, whether in the name of cow protection or anything else. Although John worked on the draft, she told IndiaSpend, “We don’t need new laws… the existing laws are sufficient to deal with these crimes.”

Gonsalves said IndiaSpend’s database must be recognised as a start point. “Citizens should now use this information to follow up it up with action,” he said, suggesting how:

- Using the data, citizens can get in touch with lawyers to help these people get justice.

- Through these lawyers, citizens may follow up on counter cases filed by assailants and the police against the victims of hate crimes, which prevent them from receiving justice.

- In cases where cases are filed against the assailants, citizens may reach out to victims to show what is called “practical solidarity”: “Find out if they and their families are doing OK, reach out through NGOs to see what help is now needed to rehabilitate their lives.”

- Citizens should also use this data to find out at what stage a case is currently at and help victims take appropriate preventive action: “Find out if all the assailants have been released. In most cases they are, then they go to victims and threaten them to withdraw the cases or face further consequences.”

- Come forward with information that can serve as ‘action alerts’ for their respective areas: “For example, whenever a countersuit is filed or an assailant is released, people should come forward to give information, notify the larger community who may then follow this up by writing to the National Human Rights Commission and the state director general of police.”

“This [database] has to expand and become more proactive and actionable. The legal system can be oppressive. These cases of violence stay with the victims for a long time – very often when the prosecution sides with the assailants – victims do not receive justice for six-eight-ten years at a stretch,” Gonsalves told IndiaSpend.

Alison Saldanha is assistant editor with IndiaSpend.

This article originally appeared on IndiaSpend, a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit. Read the original article here.