“One of the most infuriating habits of these people was their love of superfluous words,” thinks the colonial district commissioner to himself in the final chapter of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. It is from the only section of this groundbreaking novel that is not written from the perspective of Africans. Telling of the colonisation of the Igbo from their point of view, the line foreshadows much: how colonisation will attempt to write African perspectives, deemed “superfluous”, out of their own histories, but also that, “infuriatingly” enough for an oppressor, the colonised Africans wield words of their own.

The great African novel? Credit: Paull Young via Flickr, CC BY-SA

Published 60 years ago this year by Heinemann in London, Things Fall Apart has sold more than 10m copies and been translated into more than 50 languages. It follows Okonkwo, a renowned warrior from a fictional Igbo village in early 20th-century eastern Nigeria. In straightforward and evocative prose, Achebe depicts how a culturally rich and well-governed society is destabilised by the arrival of Christian missionaries and British colonialists. Okonkwo is a flawed hero, but his attempts to confront the forces transforming his village speak to a long history of anti-colonial resistance.

Now considered essential reading in many African Studies and English Literature courses, Things Fall Apart can hardly be dissociated from the emergence of the African novel and modern African writing in general. However, Achebe’s debut also sparked a formative debate on language and African literatures. With English so intimately entwined with colonial history, the fact that the novel hailed as inaugurating a modern, independent Africa’s literature was also written in English became a point of contention. Was Things Fall Apart upholding a Western model, or confronting and subverting it?

Also Read: African Literature’s Unending Battle With the Language Question

Language is power

Language is never ahistorical or apolitical, but it carries an especial charge in post-colonial contexts. Educational, administrative and religious institutions had conducted life in the colonies in the language of the coloniser. Speaking it would often mean access to privileges, while speaking only African languages could mean economic disadvantage at best, physical punishment at worst. With this history in mind, Achebe and his contemporaries had to ask: did reaching global audiences to challenge their perceptions about Africa matter more than enriching their own languages by helping African readerships flourish?

The debate extended beyond the question of use and reach: it was also about post-colonial identities. Language provides the names, value systems and and discourses by which we “know” our world and ourselves. A dominant language dominates the terms by which your reality is constituted. To prioritise reading and writing in European languages could perpetuate colonial structures after independence, once again delineating who could speak, on what terms, and by what criteria African writers would be judged.

Forging identity

Whether to foster post-independence African literary cultures in European or African languages fuelled the historic 1962 African Writers Conference at Makerere University in Uganda. Many of its participants went on to become well-known literary voices from the continent. These included the first African Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, a Nigerian poet and playwright; Grace Ogot, one of the first Anglophone female Kenyan writers to be published; and Christopher Okigbo, who together with Achebe established Citadel Press. Also prominent were Kofi Awoonor, a Ghanaian poet and diplomat who was among those killed in the 2013 attack in Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi, and Lewis Nkosi, whose literary career in exile from South Africa spanned nearly every genre.

There was division on the issue. Kenyan playwright and academic, Ngugi wa Thiong’o – then a student at Makerere – believed that the restoration of cultural memory rested on rehabilitating mother tongues. Now a major voice in African letters who writes mostly in Gĩkũyũ, Ngugi argued that, without this “decolonisation of the mind”, they would otherwise be forever living by moral, ethical and aesthetic values not their own.

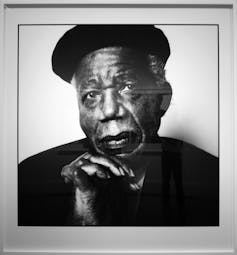

Portrait of Chinua Achebe. Credit: Steve Pyke (2008) New Yorker, CC BY-SA

Born into a family of Christian converts in eastern Nigeria in 1930, Achebe was educated in local Anglican schools and went onto become one the first graduates of the University of Ibadan. So English was indeed a part of his identity in ways not every Nigerian would have shared. But Achebe was therefore all the more aware that education and religion were complex facets of colonialism. Things Fall Apart dramatises this with nuance in the character of Nwoye, who rebels after his brother’s death by converting to Christianity.

Achebe advocated a “both” rather than an “either/or” approach in his 1965 essay “The African Writer and the English Language”. He argued that the African writer, in “fashioning out an English which is at once universal and able to carry his peculiar experience”, would bring about a far more subtle rejection of the historical dominance standard English represented.

Clearing ground

Ultimately, English was one factor that helped Things Fall Apart, as it did other works of African literature, to transcend national boundaries for six decades. But these probing political and cultural questions were carried right along with it – and they informed a legacy of African thought on the meaning and purpose of literature, which the continent’s contemporary voices can stand on today.

When African writers choose to contribute to literatures in their mother tongues, this can only be positive. But when they chose to reach the world’s Anglophone readers, it is as Achebe envisioned it: with “a new English, still in full communion with its ancestral home but altered to suit its new African surroundings”.![]()

Sarah Jilani is a PhD Candidate in the Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.