Hyderabad: An extradition case involving a Ukrainian oligarch who has business connections to both Russian president Vladimir Putin and US president Donald Trump’s former campaign manager is likely to turn the focus back towards a now-forgotten mining scandal in Andhra Pradesh that involves a senior Congress politician with cross-party connections so extensive that no government seems eager to dig very deep.

Over the past few months, the American effort to secure the extradition from Austria of oil and gas magnate Dmytro Firtash – facing allegations in the United States that he led a conspiracy to pay $18.5 million in bribes to Indian officials to facilitate a $500 million titanium project in Andhra Pradesh – has taken many twists and turns.

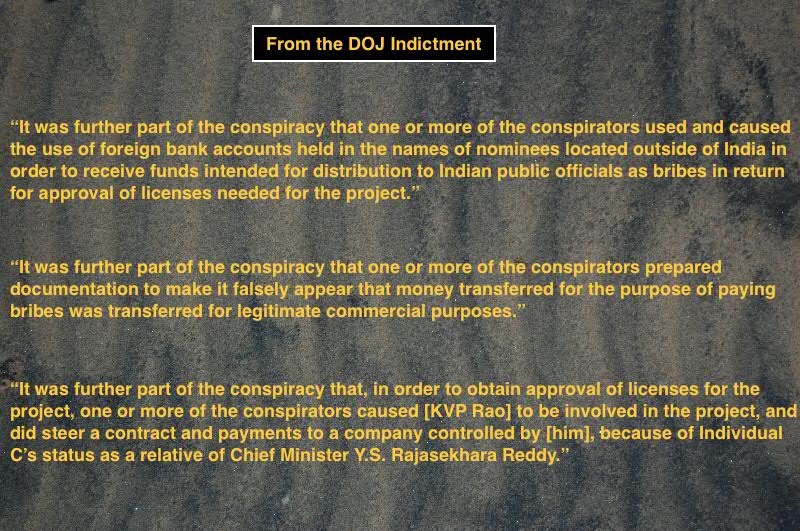

In April 2014, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) made public the indictment of six people including Firtash and Congress Rajya sabha MP K.V.P. Ramachandra Rao aka KVP, described in US court papers as “a close advisor to the now-deceased chief minister of the state of Andhra Pradesh, Y.S. Rajasekhara Reddy.” The indictment was dated June 2013.

Companies controlled by Firtash, the indictment said, were involved in a titanium sponge project that “required licenses and approval of both the Andhra Pradesh state government and the central government of India … The approval and issuance of such licenses were discretionary, non-routine governmental actions… (The) defendants used US financial institutions to engage in the international transmission of millions of dollars for the purpose of bribing Indian public officials to obtain approval of the necessary licenses for the project.”

Despite this indictment, no investigative agency in India has seen fit to question Rao – not during the tenure of the Manmohan Singh government at the centre, which demitted office one month after the US indictment was unsealed, or since the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in May 2014.

Firtash was arrested in Austria on March 12, 2014, at the request of the Federal Bureau Investigation. A week later, he was released on a bail of €125m (£105m, $172m), the largest in Austrian legal history, but was asked not to leave the nation.

Firtash challenged US attempts to have him extradited and on April 30, 2015, a local court ruled in his favour. The judge held that more than a year had passed since the Ukrainian oligarch’s arrest in Vienna and that the US DOJ had not provided sufficient evidence to show that he had paid bribes in India. In particular, the court said that the US had not passed witnesses interview protocols.

The DOJ moved the Vienna court of appeals and on Tuesday, February 21, 2017, judge Leo Levnaic-Iwanski ordered Firtash to be extradited to the United States to stand trial in Chicago on bribery charges. The judge noted that the US authorities had provided additional documentation after the lower court’s order.

Firtash faces up to 50 years in prison and the seizure of all his assets if the case in Chicago eventually goes against him.

Before he could be put on a flight to the US, however, the Austrian authorities arrested Firtash on a Spanish arrest warrant related to charges of money laundering.

Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash arrives at court in Vienna, Austria, February 21, 2017. Credit: REUTERS/Heinz-Peter Bader

According to The Guardian, the prosecutor’s office said the arrest was due to supplementary information received from the Spanish authorities, raising the possibility that the oligarch may be extradited to Spain rather than the US, or at least to Spain before he eventually being moved on to Chicago.

“The case has taken on an extra dimension of geopolitical interest because the businessman is a one-time partner of Paul Manafort, formerly Donald Trump’s campaign manager,” the daily reported.

But it also a political hot potato in India given the alleged involvement of KVP and the yet-to-be-uncovered trail of payments that Firtash is said to have made to Indian officials and politicians.

Government inaction

Largely driven by US domestic statute that makes it an offence for American companies to bribe foreign officials, US investigative agencies have have played a major role in unearthing corruption cases involving Indian individuals.

In July 2015, the DOJ unearthed the Louis Berger bribery scandal, prompting the Indian authorities to swing into action and make arrests. The enforcement directorate (ED) even raided the residence and offices of Goa’s ex chief minister Digambar Kamat and his associates and relatives. Last year, the DOJ was instrumental in unearthing Brazilian defence firm Embraer’s bribery to Indian middlemen, which is currently being investigated by Indian authorities.

One reason that Firtash’s bribery case, and its connection to India, has largely been a much quieter affair is because the main accused is a prominent politician who is connected across party lines.

The charge against Rajya Sabha MP KVP Ramachandra Rao is that from 2006 onwards, he and five others “allegedly conspired to pay at least $18.5 million to Indian officials in bribes to secure licences to mine minerals in Andhra Pradesh”. Over $500 million in sales was expected to arise from this particular mining project, with a portion of titanium sales preferentially allocated to one unnamed “Company A” (identified as Boeing in US news reports). A number of international companies coordinated this enterprise, including Group DF Limited, a British Virgin Islands firm controlled by Firtash.

The National Central Bureau (NCB)-Interpol CBI, in its writ petition dated September 2, 2014, filed in the Hyderabad high court (common for both the state of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh), admitted that information had been received that from January 2005 to June 2013, Rao and the others were members of a criminal enterprise to establish a beach sand mining project in the state of Andhra Pradesh.

“The leader of the criminal enterprise authorised the payment of at least $15.5 million in bribe to officials of both the state government of Andhra Pradesh and the central government of India to secure the approval of licenses for the project,” S.P.S. Dutta, assistant director NCB-Interpol, said in his submission to the court.

The writ petition also said that US-based financial institutions were used to engage in the international transmission of millions of dollars for the purpose of bribing Indian public officials in connection with obtaining approval of the necessary licenses for the project. “A member of the criminal enterprise travelled on two occasions between Chicago, Illinois and Greensboro, North Carolina, in order to conduct money laundering transactions for the interests of the enterprise’s illegal activities,” the petition said.

The Interpol General Secretariat (IPSG), Lyon, France also published a ‘red corner notice’ against KVP Ramachandra Rao on April 11, 2014. This notice was issued after Firtash’s arrest on March 12, 2014. However, KVP challenged this and obtained a stay. On April 28, 2014, the high court asked the CID to refrain from proceeding further on the Interpol notice issued against Rao. The court also issued similar notices to the centre and the CBI.

In its writ petition, NCB Interpol told the court that it is a part of the CBI and acts as an interface between various law enforcement agencies in the country and the NCB of other countries to mutually combat crime and trace fugitives. The NCB also submitted the court that it is not vested with any police powers. It also pleaded with the court to dismiss the interim order it issued on April 28, 2014.

In KVP Rao’s submissions, which Dutta’s affidavit notes, the MP claimed the case was the result of political rivalry. He also made the claim that the Interpol stemmed from the claim that US laws had been broken but that these did not apply to Rao, who was an Indian citizen. Dutta’s affidavit rejected all of Rao’s objections.

In its notice to the CBI and the centre, the high court asked them to file counter-affidavits, with the case to be adjourned “till after summer vacation”. Since then, there has been scant progress in the matter.

However, now that the Vienna appeal court has upheld the US extradition request and made it clear that the Chicago court had submitted valid documents and information as evidence, the Indian side of the criminal case is unlikely to remain dormant for long.

Everybody loves KVP

Who exactly is K.V.P. Rao? By all accounts, he was a confidante and close friend of the late Congress politician Y.S. Rajasekhar Reddy (YSR), who was chief minister of Andhra Pradesh from 2004 till his death in a helicopter crash in 2009. Within the state’s bureaucratic circles, it was widely known that no major file moved without first being looked at by Rao – described by YSR as his conscience (‘aatma‘). It didn’t matter whether the file was for construction of medical colleges, mines, power projects or industrial corridors. As a shrewd political strategist, Rao, who held the formal title of advisor to the CM on political affairs until 2008, served as a major link not only within state politicians, but also in Delhi.

At all times, before and after the Andhra Pradesh-Telangana bifurcation, Rao has been a kingpin for the Congress. The party rewarded him with a Rajya Sabha membership in 2008, and renewed his term in 2014. While Rao’s power may have dimmed over the years, his advice is still a must for the Congress in both Telugu-speaking states today thanks to his relationship with various communities and leaders. His son, Kotagiri Ujwal, is married to Indira Priyadarshini, daughter of K. Raghu Ramakrishana Raju. Raju, once a close associate of YSR’s son, Y.S. Jaganmohan Reddy, is now a prominent Bharatiya Janata Party leader in coastal Andhra Pradesh. If he is related by marriage to a senior BJP leader, KVP continues to be close to Jagan of the YSR Congress. Andhra Pradesh chief minister Chandrababu Naidu’s aides also concede that he has good relations with KVP.

KVP Rao is also an important politician in Telangana too. He belongs to the Velama community, to which chief minister K. Chandrashekhar Rao (KCR) also belongs. Congress leaders have accused KVP of being behind KCR’s political moves. KVP is also very close to most media houses, both regional and national, in Hyderabad. In a nut shell, KVP is well connected to the BJP, Congress and YSRCP, and has excellent relations with the two ruling parties of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

What next?

Rao’s role in the Firtash bribery case will come back to the political centre-stage once the Ukrainian oligarch is extradited to the US and put on trial.

As and when it gets underway, the Chicago trial will rake up the decade-old titanium mining case and raise questions about where the payoffs went and why the NDA government has dragged its feet over the matter. Though the DOJ indictment helpfully confirms that “there were in force and effect [at the time the alleged acts were committed] criminal statutes of the Republic of India prohibiting bribery of public officials, including the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988″, the governments of India, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have shown no interest in launching a probe.

Gulam Shaik Budan is a Hyderabad-based investigative journalist.