In an effort to get around Russia’s ever stricter protest regulations, people often take turns holding banners in one-man pickets. People go for “walks” instead of marching. People ride the metro with signs pinned to their bags. And now in lockdown, Russians are channeling their discontent into virtual demonstrations.

On Tuesday, various opposition groups plan to hold an online protest against planned constitutional reforms, which could keep Russian President Vladimir Putin in power until 2036, far beyond his current term limit. The organisers of the protest, dubbed “For Life,” are also demanding “urgent measures to save people and the country during the crisis” that has resulted from the coronavirus pandemic.

The event will be streamed on YouTube, with several prominent opposition figures speaking. Participants can send in pictures of themselves holding banners for use during the rally. And the organisers are also calling on people to “gather” virtually in their cities on Yandex.Maps, the Russian equivalent of Google Maps.

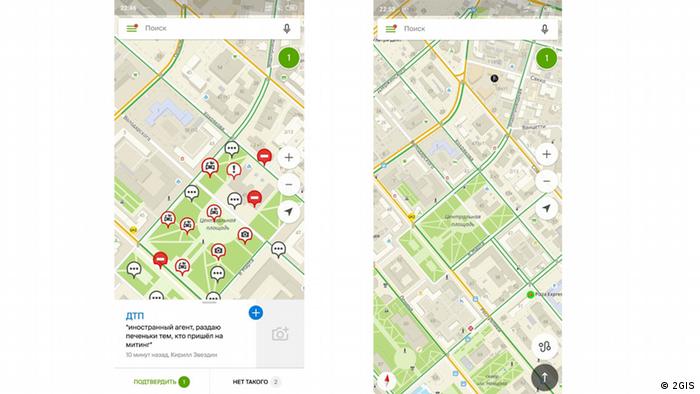

The new grassroots method of protesting sprung up early last week, when people around Russia began tagging themselves on virtual mapping programs outside government buildings in their cities. On Yandex, they used a function — designed to warn users about traffic jams — to type out their anger and fears. “People don’t have anything to eat. Where are the people’s payouts?” wrote one Moscow user. “We can repeat 1917 [The Bolshevik-led revolution — Editor’s note]” one user near the Kremlin warned, as others called for Putin’s resignation.

The virtual map protest started in the southern city of Rostov-on-Don last Monday and spread across Russia to cities including Nizhny Novgorod, Novosibirsk and Yekaterinburg:

В Екб тоже виртуальный митинг в Яндекс.Навигаторе pic.twitter.com/vAbk6ssDCU

— Dmitry Kolezev (@kolezev) April 20, 2020

Yandex soon began deleting the comments, explaining that “messages that are not related to the traffic situation or that contain swearwords have always been moderated and deleted.”

The spontaneous wave of online activity has made the organisers of the upcoming online opposition protest hopeful that their audience could expand. “Even though we can’t take to the streets, the number of people who are dissatisfied is only growing,” said Andrei Pivovarov, one of the protest’s organisers and the director of the organisation, Open Russia.

New frontiers?

In Russia, opposition protests rarely reach beyond Moscow and St. Petersburg. But in the Siberian city of Tyumen, Nikita Kyshko, one of the regional organisers of the campaign against constitutional reforms, is hopeful that can change. The local activist says that in his city of 600,000, turnout at protests has never exceeded several hundred people in the past few years.

“The quality of life here is just above the average for Russia. So people think: ‘Why bother?,'” he explains, adding that many are also afraid to protest. He thinks people may have fewer inhibitions online, despite increasing government control over the internet. Last week Tyumen was one of the cities that joined virtual protests on mapping apps. “This way, people see that they aren’t alone,” Kyshko says of the virtual demonstrations.

And Kyshko believes the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic could turn even staunch government supporters. “This situation is opening people’s eyes. The government has left the people to fend for themselves.”

Far from rosy

Last week, Putin admitted that while the coronavirus poses a serious health threat to Russia, the pandemic’s “impact on the economy, on entire sectors, is just as dangerous.”

Russia’s central bank has predicted the country’s GDP will likely shrink by between 4% and 6% this year, potentially wiping out years of growth, due to the impact of falling oil prices and the consequences of Russia’s lockdown measures.

Putin initially announced a “non-working” period at the end of March, with many businesses forced to close but continue paying their employees. The government has been phasing in financial support for individuals, families and businesses. But direct cash injections have been limited and sometimes hard to access. According to IMF estimates, the total cost of Russia’s fiscal support package is currently at 2.1% of its GDP, a fraction of what many other G20 countries are pumping into their economies.

Also Read: Lenin in Urdu: His Every Word Became Poetry

Boiling over?

Now some are looking online for an outlet for their frustration. When asked about the spontaneous Yandex protests last week, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said “we pay great attention to messages in which people are talking about their difficulties,” but added that the importance of the Yandex messages shouldn’t be overplayed.

But Alexander Kynev, a political scientist, believes officials in the Kremlin may be more worried than they are letting on. “They know that as soon as the restrictions are lifted the dissatisfaction that is building up now will spill over from the online into the offline world,” he said. Last week, several hundred people in Russia’s North Caucasus region of North Ossetia took to the streets in the regional capital, Vladikavkaz, breaking self-isolation measures to rally against the local authorities.

Sociologist Denis Volkov, from the Levada Center, an independent Russian pollster, also thinks the new online protests are a “short-term phenomenon” and potentially a placeholder for offline demonstrations.

Surveys by Levada found that at the end of March only 8% of Russians were willing to take part in a street protest, while 86% said they probably wouldn’t. But Volkov believes that dissatisfaction among the population is likely building. He compared the current situation to previous economic crises to argue that people may take to the streets later.

“At the beginning of a crisis there usually aren’t protests. People are busy trying to adapt to the new situation,” he said. “Protests or a willingness to protest usually come a few months later — if the situation hasn’t gotten better.”