Muhammad Ali Jinnah has left behind a wound in India that will not heal. He was responsible for the partition of the country on the basis that Hindus and Muslims were two separate “nations”. Hence, he argued, the Muslims were entitled to a separate, sovereign state carved out of British India that would be their ‘homeland’.

Jinnah’s creation – Pakistan – was born in a frenzy of violence and bloodshed as several million people on the wrong side of the newly defined border were compelled to leave their homes; a million of them were killed, while several hundred thousand were wounded and violated. Injuries to the mind and spirit remain fresh, while communal animosities fester and continue to define contemporary politics in South Asia, as they had done nearly a century ago.

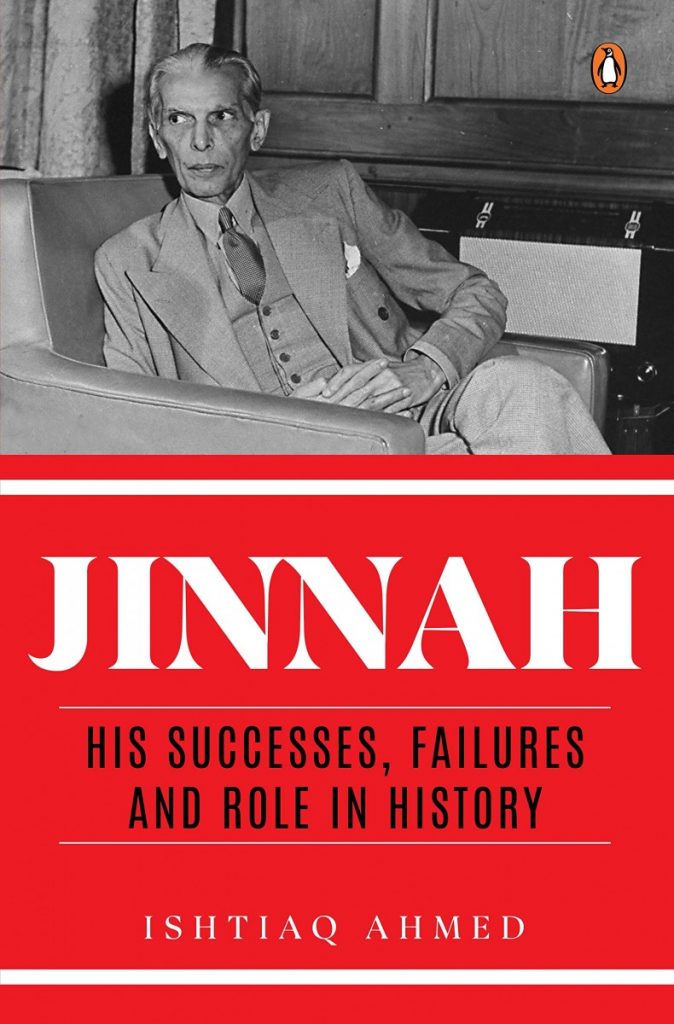

Ishtiaq Ahmed

Jinnah: His Successes, Failures and Role in History

Penguin Viking (September 2020)

Ishtiaq Ahmed, the author of this latest monumental study, Jinnah: His Successes, Failures and Role in History, is a scholar of Pakistani origin who holds a senior academic position in Stockholm University and also teaches in Lahore. He has authored several works on various aspects of Pakistan’s history and politics, including a substantial book on the country’s armed forces and their central position in national affairs.

There are several well-known works on Pakistan’s founder and venerated Quaid-e-Azam (‘great leader’) that have discussed the extraordinary rise of this little-known lawyer to national status in the last decades of the freedom struggle. During this period, he engaged as an equal and matched wits with stalwarts such as Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, successive British viceroys – Linlithgow, Wavell and Mountbatten – backed by the imperial power of the UK, and diverse members of the Indian Muslim community whose leader and ‘sole spokesman’ he finally became in 1937 and obtained for them their cherished homeland 10 years later.

The author’s justification for this work is that most writings on Jinnah have been based on a “complete neglect on primary source material”. This book is largely based on Jinnah’s speeches and public interviews throughout his career, which Ishtiaq Ahmed uses to explain the evolution of Jinnah’s position on national issues, alongside his steady elevation on the national landscape.

Jinnah’s career

Jinnah’s political career, as set out in this book, follows a familiar trajectory: it can be conveniently divided into four parts: one, when he was an Indian nationalist and a member of the Indian National Congress; two, when he started moving towards Muslim nationalism; three, his firm commitment to realising an independent Pakistan, and, finally, his short period as Pakistan’s head of state.

The first issue that concerns students of the sub-continent is: what turned Jinnah the Indian nationalist and an important role-player in the Congress into an ardent enthusiast for Muslim interests? In the second decade of the last century, Jinnah straddled both the Congress and the Muslim League and even helped bridge Hindu-Muslim differences through the Lucknow Pact of 1916. Ahmed says the reasons for Jinnah’s disenchantment with the Congress were not ideological but personal and “strategic-tactical”, and both have to do with Jinnah’s interactions with Gandhiji.

Also read: How Jinnah Dismissed Congress’s Minority Rights Proposals to Justify Two-Nation Theory

Things seem to have gone wrong between them from the very first meeting itself in 1915, when Gandhi had been back in India from South Africa for a year. While Jinnah was fulsome in his praise of Gandhi’s achievements in South Africa, the latter seems to have described Jinnah as a Muslim rather than as a national leader. At a later meeting in 1917, Gandhi asked Jinnah to address his (Gandhiji’s) supporters in Gujarati; Jinnah was heckled when he spoke in English.

Finally, in 1920, true to form as an English gentleman, at the Nagpur session of the Congress Party, Jinnah referred to Gandhiji as Mr Gandhi and Maulana Mohammed Ali Jauhar as Mr Mohammed Ali, without the honorifics of respect due to them. Jinnah had then to endure fierce heckling and even threats; he walked out in protest and “never returned”. Ahmed believes that Jinnah saw these experiences as attempts by Gandhi to deny him access to the top positions in the Congress party.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah with Mahatma Gandhi. Photo: Wikipedia Commons.

The final parting of ways occurred over the Khilafat movement: Gandhi wanted to launch a non-cooperation movement on this issue. Jinnah viewed this as an assertion by Gandhi to make the freedom movement a mass movement, a scenario in which Gandhi would be the leader rather than Jinnah, who backed a steady progress towards self-rule. Ahmed points that, “with Gandhi’s rise the Congress was radicalised in a way Jinnah found difficult to adjust to [and] he was not willing to play second fiddle to Gandhi or anyone else”.

If this assessment is correct, there is a juicy irony in the situation in that Jinnah, eschewing mass politics, himself became a mass leader of Muslims and came to match Gandhi in populist rhetoric and popular agitations.

Leader of Muslims

Jinnah’s ascent up the ladder of communal politics was slow. The Nehru Report of August 1928 was an attempt by the Congress to produce a document that would set out a “constitution” for India with “dominion status”. It provided for joint rather than communal electorates and reservation of seats for minorities in a federal set up, with a strong centre. Ahmed points out that this report “enjoyed broad consensus among leading Indians of all communities”.

Jinnah summarily rejected this report and instead put forward his “Fourteen Points” in March 1929. Ahmed calls the political set up that Jinnah envisaged a “quasi-confederation”, with a weak centre and most powers vested in the provinces. This approach consolidated the divide between Jinnah and the Congress – Jinnah asserted he represented all Indian Muslims who were a “nation” not just a minority, while the Congress viewed India as a unified nation, with its diverse communities’ interests being reflected in the political order through constitutional means.

Ahmed points out that from 1929, Jinnah made the British his partners in his communitarian agenda. Recalling that in January 1929 the Congress had issued a call for ‘Poorna Swaraj’, full independence, Jinnah told Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald to grant India dominion status rather than independence, while warning the prime minister that independence enjoyed considerable support in India.

However, at this point, while the British were anxious to counter Congress’ vision of a united India by focusing of domestic religious and other divisions, they had other more prominent Muslim leaders they could depend on. This changed with the beginning of the Second World War, when the Congress made its support for the British war effort conditional on the grant of independence and then followed this up with the ‘Quit India’ movement from August 1942.

As Congress leaders and thousands of their followers went to prison, Jinnah emerged as the great British ally. Ahmed notes Linlithgow saying that “Jinnah’s offer of help proved crucial to retaining effective control over India” – if the Congress and the League had been together, British rule would not have survived.

At this stage, Jinnah became the most influential exponent of the two-nation theory – the idea that Hindus and Muslims constitute two ‘nations’ who could not live together, and attempts to impose unity would lead to civil conflict. Ahmed has correctly noted that Jinnah’s idea of ‘Muslims’ – projecting an undifferentiated, monolithic collective – was an artificial construct and had no basis in reality, ignoring as it did the extraordinary diversity of origin, wealth, social class and even caste that informed the community.

British support for Jinnah

Ahmed’s account of Jinnah’s political leadership makes it abundantly clear that Jinnah’s Pakistan project was crucially dependent on British support and that it would not have been realised but for the backing it received from British officials in India and London. He also notes that British intelligence destroyed numerous secret documents before the transfer of power that conceal its robust support for partition.

The book points out that, despite the pressure exercised by the freedom struggle, the British rulers of India had no intention of relinquishing their control over their jewel in the crown; the most they were willing to consider was some limited form of self-rule, but with authority remaining firmly with Britain.

Ahmed traces the story of Britain retaining its imperial interests back to 1930 when Winston Churchill launched a fierce attack in parliament on Hinduism and the Hindus, saying that the British had saved India from barbarism; British rule was, therefore, good for India. The author makes several references to “rumours” of a secret arrangement between Churchill and Jinnah, going back to 1940, in which Churchill “had pledged to reward Jinnah with Pakistan for the support to the war effort”.

While there is no documentary support for this purported agreement, Ahmed. Writes that there is enough evidence to affirm that both Linlithgow and Wavell were viscerally hostile to the Congress and supportive of the Muslim League.

While the Congress and Jinnah were engaged in an existential communal struggle, the British were quietly looking at their strategic interests after the war and calculating how they could be best served. Their assessment was that after the war a united India (as shaped under the Cabinet Mission Plan – weak centre and accommodation of communal identities in the constituent assembly and the provincial legislatures) would best serve British interests. But, Ahmed adds, “if British interests were served better by Partition, then that had to be considered and the distribution of territories between India and Pakistan worked out carefully”.

By May 1947, the British top brass had accepted the need for partition. It was noted that West Pakistan would serve Britain’s strategic interests by providing Karachi port, air bases and Muslim manpower when required. They also insisted that this Pakistan should be weak – much weaker than India – so that it would continue to depend on western support – military, political and economic – to sustain itself.

Hence, they rejected Jinnah’s maximalist territorial demands – for the provinces of Punjab and Bengal and a corridor linking the eastern and western parts of the country. Partition on this basis thus became the British endgame in the sub-continent; Jinnah’s agenda for a Muslim homeland, albeit truncated and “moth-eaten”, was thus achieved.

The book ends with a short 50-page overview of Pakistani developments up to the election of Imran Khan as prime minister. Ahmed writes that the Islamist features Pakistan has acquired would have shocked Jinnah, but they were “inherent in the two-nation theory … and all the Islamic ideas and images Jinnah had invoked to embellish his Pakistan as an ideological Muslim democracy”.

Ishtiaq Ahmed’s Jinnah

This is not a personal biography of Jinnah, but a fresh look at his thinking and actions in the run-up to partition and his short stint as governor general of the new state of Pakistan.

In his assessments, Ahmed is scrupulously balanced and fair. He sharply criticises Jinnah on several important points and upholds the positions adopted by Gandhi and Nehru. This is thus not an unabashed hagiography of the founder of Pakistan. At the same time, the author critically examines certain contentions made by other prominent writers and provides his own considered views. This work is thus an essential source for all students of modern South Asian history and politics.

There are just a few places where I wish more details or better clarifications had been provided. The date for the transfer of power was moved from June 1948 to August 1947. Ahmed merely says that this “must be blamed on Mountbatten”. Linked with this is why the administration did not anticipate the carnage accompanying the transfer of populations and then found itself totally unable to handle the violence.

The discussion of the Kashmir is unsatisfactory. Ahmed merely quotes the information that Col Iskander Mirza shared with Sir George Cunningham, the governor of the North-West Frontier Province, on the subject of the tribals’ raid into Jammu and Kashmir. This includes the sentence: “Jinnah himself heard of what was going on about fifteen days ago” but asked that he not be given any further information; “My conscience must be clear”, he is quoted as saying.

Also read: Language Politics in Jinnah’s Pakistan Has Parallels in Modi’s India

This is surely a very curious position for the head of state of Pakistan. Obviously, Jinnah had full knowledge of the raid, which was in keeping with his numerous peremptory and ill-thought out actions as governor general. In fact, a few days later, we see him justifying the incursions and wanting to send regular Pakistani troops into Kashmir and the British commander-in-chief backing him.

While the matter of Pakistani intervention in Kashmir is largely based on secondary sources, Ahmed spends some space discussing a possible “swap” arrangement in which Pakistan would drop all claims on Hyderabad in return for Jammu and Kashmir; this was firmly turned down by Jinnah himself. Jinnah’s secretary KH Khurshid says that Jinnah might have been “playing for some higher stakes”, but these are not clarified. Given Jinnah’s long and close links with the British, we can suspect these “higher stakes” might have involved British machinations in support of Pakistan – possibly the backing given by the British to the Pakistani case on Kashmir at the UN.

Jinnah’s persona and legacy

More than 70 years after his death, Jinnah remains an enigmatic and controversial figure. Since this book is a political not a personal biography, we only get occasional vignettes of his personality during specific episodes. While discussing Jinnah’s interviews with Beverly Nichols, Ahmed speculates that Jinnah’s “cerebral attitude and very English manners” could have appealed to Nichols. But this is the same courtly Englishman who in some of his public remarks spoke in crude verse and caricatured Hindus as treacherous.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

We also know that Islam, the faith, rested very lightly on this champion of the Muslim community: Ahmed believes that Gandhi “sensed that Jinnah’s enthusiasm for Islam was political rather than a change of heart towards piety”. Jinnah is known to have enjoyed alcohol and rarely joined in any Shia ceremonies or attend congregational prayers.

The man’s persona and his achievement are so far apart that scholars still struggle to understand Pakistan’s Quaid-e-Azam. An early biographer, Hector Bolitho, described Pakistan as the fruit of his “imagination and persistence”. A later writer, Stanley Wolpert, noted that Jinnah had successfully altered the course of history, changed the map of the world, and had created a nation-state.

But here there is need to pause for further reflection.

While pursuing the Pakistan project, Jinnah was obsessively single-minded and even egomaniacal, spurning every overture and every Congress proposal for mutual accommodation.

Ishtiaq Ahmed says that in achieving Pakistan, Jinnah “out-witted and out-manoeuvred” Congress stalwarts Gandhiji and Nehru. But this does seem right; they emerge from this narrative as men of vision, with a commitment to larger values and a desire to keep diverse communities of the sub-continent together. In fact, Ahmed makes it clear that Jinnah did not obtain Pakistan; it was a poisoned chalice imposed on South Asia by British imperialism.

After independence, while India shaped a modern democratic and secular nation, despite the trauma of partition, Jinnah appears bitter, vindictive and paranoid. Having no ideas on nation-building, he is authoritarian and capricious, obsessively seeing threats to the state he heads.

Jinnah as governor general of Pakistan comes out as directionless on what values or belief-system to impart to the state he had obtained on the basis of a contrived homogenous communal identity that has no basis in reality. As he imposed Urdu as the national language upon the country, did he even have a clue about the background of those whom he had overnight made into ‘Pakistanis’?

Jinnah failed the people of Pakistan both domestically and globally. He did not instil into them a sense of national unity and national purpose. He failed to address the issue of whether Pakistan is a Muslim state or a Muslim homeland, opening the gates for the world’s worst fanatics to commit heinous crimes in the name of their faith. He destroyed national unity by refusing to see the absurdity of the geographical construct he had achieved as “Pakistan”. And this nation is also permanently tied to Western powers and is condemned to serve their interests – for which it was in fact created.

Jinnah has placed his country in a state of permanent confrontation with the body from which it emerged – beginning with the Kashmir incursions during his own leadership. In the absence of any acceptable idea of Pakistan the Quaid-e-Azam could shape, his successors have defined themselves in terms of “othering” India, a construct that has led to military conflict and cross-border faith-based terrorist activity.

This blood-letting, added to that took place at Partition, could justifiably give Jinnah the well-earned sobriquet, “Qatl-e-Azam”.

Talmiz Ahmad is a former diplomat, and holds the Ram Sathe Chair for International Studies, Symbiosis International University, Pune, and is also a Consulting Editor, The Wire.